The Business School of Hard Knocks

Success in business is usually attributed to a combination of luck, vision, and hard work. What success John Houston achieved in his business career – and it was no more than moderate – could just as easily be ascribed to sharp practice, larceny, and possibly even electoral fraud. In the twenty years he spent wandering the mining camps and boom towns of America, he was undoubtedly exposed to many examples of all six. That some amount rubbed off on him is likely, but the various proportions of each remain in doubt. Hard work he was always capable of and practiced throughout his life – indeed it was the indirect cause of his death. And no one would accuse him of lacking in vision. Luck, on the other hand, may have evaded him for some time – although he never stayed in one place long enough to allow any significant amount to attach itself. Hard drinking, a fierce temper, and the conviction that things were probably greener on the other side of the hill may also have prevented him from recognizing luck whenever it did appear. As for the other three – he was accused of them often enough, always denied them, and was never convicted in any court of law. In the court of history, however, the jury is still out.

During his twenty years of wandering, beginning in 1865, Houston’s business ventures were mostly in real estate. In the mining and smelter town of Hailey, Idaho, for example, while working as foreman for The Wood River Times, he came to own three cabins which reportedly earned him rental income of $130 a month. His restless nature, however, prevented him from building on his success and he moved on to Butte, Montana after only a few months. And that remained the pattern of his business life – newspaper work as a wage earner, a little dabbling in real estate speculation, and the occasional foray into the hills as a prospector.

Getting Serious

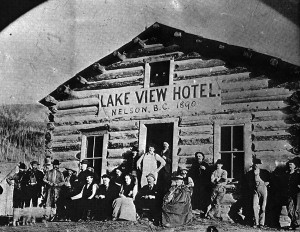

Only after reaching Nelson did Houston put his entrepreneurial talents to work for an extended period of time. His business model was simple and highly effective – use The Miner as a platform for the promotion of the town in general and the sale of his real estate properties in particular. His newspaper associates, Ink and Allen, were also partners in his real estate business and as Allen was also a Notary Public they were able to provide a kind of “one-stop shopping.” – a customer could read about available land in The Miner, publish an application for purchase (required for government land), buy a lot from Houston, and have the paperwork drawn up and notarized by Allen. With these advantages, the business flourished and accounted for over half of Nelson’s total property sales in their first two years.

Houston and Ink also commissioned the construction of commercial buildings. An article under the heading “IF NOT A BOOM, AT LEAST A BOOMLET,” in the April 18th, 1891 edition of The Miner illustrates how they combined news, business, and self-promotion.

There was quite a flurry in Nelson real estate this week, and several sales at good prices were reported….E.C. Carpenter, a Victoria business man, jumped in on Monday morning, and within 24 hours had purchased 13 business condition lots from John Houston and Charles H. Ink at prices ranging from $150 to $350. Mr Carpenter can double his money today by turning them at present prices…..George H. Keefer, through Houston, Ink, and Allen, sold lots 11 and 12 in block 5 (25 foot building conditions) for $600…..About half the lumber for the Houston and Ink Josephine St. block is on the ground, and the 6 stores the building is to be divided into are already spoken for or rented. A great place is Nelson and lucky are the men who own property in it.

Houston continued to sell real estate, and to use his papers to promote it, throughout his career in Nelson although his partnership with Allen and Ink ended with the sale of The Miner in the spring of 1892. This sale was the cause of the above mentioned accusations of sharp – if not down-right dishonest – practice (see John Houston: Newspaper Man, for details).

Houston also cast a wider net, buying and selling land in Rossland and New Denver, upon occasion acting as his own auctioneer. In 1898 he built The Houston Block on the same Josephine and Baker lot mentioned above and which he described in The Tribune as “one of the handsomest and most substantial buildings in the city” adding, “as to the style of architecture – well, it is Houstonian…” If he is to be believed when he claimed that the interior woodwork alone cost $13,000, he must have taken a considerable loss when he sold the 70′ by 50′ brick and marble structure just three years later for only $25,000. Today, The Houston Block is one of the heritage jewels of Baker St. and, fittingly, houses a real estate office.

Nelson Electric

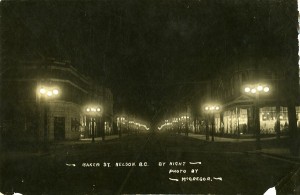

Houston’s lasting legacy, which also played a prominent role in his political career, is the creation of The Nelson Electric Light Company, born out of his desire to transform Nelson from a temporary mining camp to a stable and modern urban centre, seat of commerce and government – and to do it as quickly as possible. A water works, telephone system, and well-lit streets were all undoubted signs of prosperity and permanence and Houston was involved in the creation of all three.

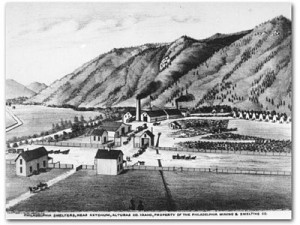

A good source of revenue for the provincial government – both above and below the table – was the sale of corporate charters for the construction of railways, canals and other industrial facilities using crown land and assets. In fact, two such charters were issued within a few days of each other, one to The Kootenay Power Company to build a tramway between Nelson and The Silver King Mine plus a hydro-electric power plant on the Kootenay River, and a second, to The NELC, to build a power plant on Cottonwood Creek for the purpose of supplying electricity to Nelson. The KPC was backed by big business – the CPR, The Columbia Kootenay Steamship Navigation Company, and Spokane industrial interests. Fortunately for Houston and ultimately The City of Nelson, the recession of 1893 as well as a much better appreciation of the financial risks and rewards involved, convinced them to withdraw.

Nelson Electric’s plan was to build a power plant at Cottonwood Falls, on the western edge of the town site, and to supply it with water via a flume from a dam built above the falls. Within a year, however, it was apparent to Houston and his small-town business partners that they had bitten off at least as much as they could chew. To begin with, hydro electric technology was entirely new – this was to be the first in BC. Moreover the necessary money and manpower to erect poles and lines throughout the city was considerable – especially as the fall in silver prices had dried up investment. But the worst news was that Gilbert Malcolm Sproat owned the land across which the flume had to travel and he was refusing to grant a right-of-way.

Sproat was ‘the father of Nelson’, a government office holder whose work was instrumental in opening up the Kootenay. To his credit, he also fought for the right of First Nations people to have enough land to remain self sufficient. Sproat had roughly marked out the Nelson town site in 1883 and surveyed it properly in 1888. Why he refused the right-of-way and how the matter was finally resolved is not clear. Whatever the reason it foreshadowed the social divide in Nelson that Houston successfully exploited at the beginning of his political career. Sproat was a gentleman, one of the respectable citizens, and apt to look down on the rough-tongued, hard-drinking Houston and the shop and saloon keepers in partnership with him. As a friend and ally of the ownership class he may have considered it almost a duty to oppose this upstart defender of the working man. Or he may just have been a jealous ‘father’ seeing his city being wooed and won by another.

In any case, squabbles and money troubles delayed the project past its completion deadline of a

year later but an extension was granted and the project, like the power it generated, sputtered on. Even when water supply, equipment, poles and wires were in place at last, and the system was finally up and running in February, 1896, the resultant illumination was frequently dim as the volume of Cottonwood Creek proved seasonally inadequate. Three years later, the incorporated City of Nelson bought the Nelson Electric from Houston and his partners for $35,400. For the full story of how this came about, see John Houston: The Politician.

And a final note in relation to the above mentioned accusations of larceny: During the 1905 mayoralty campaign, former Mayor and Alderman Frank Fletcher indirectly accused Houston of pocketing more than his share of the Nelson Electric sale money. A political opponent, Fletcher had previously been a Houston ally and director of the NEPC and was quoted in The Miner as saying, “A payment of $6,500 [from the city] was receipted but there was only $1500 to show for it. I don’t know who got the difference. John Houston had been the last manager……”