This section explores how the Doukhobors ended up in the Kootenays. It covers their years of persecution in Russia for rejecting the Orthodox Church, their transatlantic migration to Saskatchewan and what led to their eventual resettlement in the Kootenay Boundary.

The stories in this section provide a necessary context for understanding Doukhobor culture and the events that would later unfold in the Kootenays.

SECTIONS:

- The Beginning of a New Spiritual Outlook

- Early Leaders

- Early Conflict and the First Instance of the Group Being Called Doukhobors

- A Brief Opportunity To Thrive Followed by Years of Persecution and Resettlement

- New Doukhobor Leader – Peter Verigin

- Leo Tolstoy Becomes Involved in the Doukhobor Cause

- Burning of Arms

- Immigration To Canada

- Initial Years In Canada A Fracturing Community and the Pilgrimage of 1902

- Peter Verigin Comes To Canada

- Migration to Interior B.C.

THE BEGINNING OF A NEW SPIRITUAL OUTLOOK

It all began with a spiritual revolution—a movement that rejected the authority of the Russian Orthodox Church. At its core was the belief that God resided within every being, rendering intermediaries such as priests, icons, and rituals unnecessary.

Because it evolved through oral transmission amidst the peasant population of Russia, its origins remain obscure. Historians hypothesise that it began in the late 17th century since the first documented discoveries of the group come from the mid-18th century and highlight an already established sect with an “organisational structure, mature set of beliefs, a fully developed order of worship and behavioural norms.” 1

Early investigations into the group that would later be known as the Doukhobors reveal their spiritual practices and religious beliefs. According to an extensive report from the 1760s, the Doukhobors “believed in a true living God, whom they worshipped in spirit and truth.” 1 They believed in living according to “God’s law bequeathed in the Ten Commandments.” 1 However, they rejected the spiritual significance of manmade icons such as the Cross of Christ “and instead sought communion directly with God, who dwelt in every person.” 1 As a way to recognize the Holy in everyone, they “bowed to one another and kissed.” 1 Finally, instead of attending the Orthodox Church, they “gathered with one another for prayer in their homes, where they sang and recited psalms.” 1

EARLY LEADERS

While the initial instigators of the movement remain unknown, the first documented leaders were instrumental in shaping the Doukhobor culture and religion. The first of these, Sylvan Kolesnikov, guided the group from 1755-1775. He was instrumental in promoting the belief that God is within all beings. This fundamental belief shaped the practices that define Doukhobors to this day – pacifism and vegetarianism. 2 He also rejected the spiritual significance of church icons. To replace them, he introduced bread, salt, and water, symbolizing peace, hospitality and the necessary elements to sustain life.

The next leader, Saveli Kapustin, was responsible for promoting the communal way of life and worship, including communal land ownership and collective decision-making. He wrote many of the psalms still sung today. His leadership was foundational in the survival of the movement, for without a strong sense of community, it is unlikely that the people would have endured their continuous oppression. 2

EARLY CONFLICT AND THE FIRST INSTANCE OF THE GROUP BEING CALLED DOUKHOBORS

Throughout the 18th century, the sect was persecuted for disobedience toward the Orthodox Church and Tsars. They were exiled, imprisoned, and tortured for the slightest infractions.

Their disregard for clergy and formal rituals meant that they were a threat to the Orthodox, who sought to do everything in their power to suppress them. In 1785, an archbishop derisively called the group Doukhobors, meaning Spirit-Wrestlers. He intended to say that they were wrestling against the Holy Spirit. However, the Doukhobors adopted the name and inferred a different meaning: that they were wrestling with and for the Holy Spirit.

Additionally, the Doukhobors rejected the secular government, and their egalitarianism led to a refusal to treat Tsars as superior human beings with often brutal consequences. In one instance, a Doukhobor elder refused to take off his cap in the presence of Tsar Paul. As a result, Paul ordered that he be seized and “the village be set fire to on four sides.” 3 After realizing his impulsive decision would not sit well with the people, Paul revoked his instructions to burn the village and “ordered the old man to be incarcerated for life in the Spaso-Efimevsky Monastery.” 3

A BRIEF OPPORTUNITY TO THRIVE FOLLOWED BY YEARS OF PERSECUTION AND RESETTLEMENT

Once identified as an active sect by the mid-1800s, the Doukhobors faced continual torment and abuse for adhering to their principles and beliefs. Typical punishments included: having their nostrils removed, being whipped, exiled, and condemned to years of hard labour.

In 1806, the Russian Senator Lapukhin, a defender of the Doukhobor cause and renowned reformist remarked:

No class has, up to this time, been so cruelly persecuted as the Doukhobortsi, and this is certainly not because they are the most harmful. They have been tortured in various ways, and whole families have been sentenced to hard labour and confinement in the most cruel prisons.” 4

By 1801, however, under the leadership of Tsar Alexander I, the Doukhobors benefited, for the first but not the last time, from a need to settle conquered territory. Alexander permitted them to colonize various parts of the Crimean peninsula, which had been recently taken from the Ottoman Empire. Here they farmed and lived according to their principles in harmony with each other for 40 years.

Unfortunately, Alexander‘s successor, Nicholas I, was not so gracious to the Doukhobors. He viewed them as a threat and, in 1841, declared that they either convert to Orthodoxy or be exiled to the hostile, mountainous region of Caucasus. 5 Only twenty-seven Doukhobors agreed to convert, and as a result, “twelve thousand Doukhobors were deported,” forced to leave their homes and the lands they had “acquired by long years of toil.” 6

After the long, arduous journey to Caucasia, the Doukhobors found themselves in “a strange land where the soil, climate, and conditions of life were quite new and unknown to them.” 6 They were “surrounded by hostile mountain tribes and, precluded by their religious principles from using arms, even in self-defence… seemed doomed to perish without leaving a remnant.” 6

However, despite the countless hardships of their new environment, the Doukhobors miraculously came together, adapted, and prospered.

NEW DOUKHOBOR LEADER – PETER VERIGIN

Their ability to thrive in such a desolate place can be attributed to the remarkable guidance of Lukeria (Lukerya) Vasilievna Kalmykova, a beloved Doukhobor leader known for her commitment to equality and justice.

Having no children of her own, Lukeria carefully selected a young boy named Peter Vasilevich Verigin as her successor. Under her tutelage, Peter honed his skills and studied the Doukhobor principles for many years, preparing to carry forward her legacy.

Lukeria passed away on December 15, 1886. The majority of the Doukhobors supported Peter Verigin as her successor but a small party, led by Lukeria’s brother, orchestrated Peter’s arrest shortly after his declaration as leader and had him exiled to Siberia, leaving the Doukhobors once again in turmoil.

Peter’s exile, far from dampening the spirit of the Doukhobor community, only fueled their determination. Under his continued communication and guidance, they emerged stronger, steadfast in their commitment to their core principles and beliefs.

LEO TOLSTOY BECOMES INVOLVED IN THE DOUKHOBOR CAUSE

While Peter Verigin encouraged the community to stick to their founding beliefs, his leadership also marked the introduction of a new set of principles influenced by Tolstoyan philosophy.

Peter Verigin was the spiritual leader of the Doukhobors and Leo Tolstoy was the philosophical mentor. He influenced the direction of the community overtly through his relationship with Verigin and through his followers, who lived among the Doukhobors for many years in Transcaucasia and later in Canada.

Tolstoy was a man consumed by musings on morality, religion, and the pursuit of human perfection and became particularly interested in the physical application of his philosophical and political ideals. He developed “a radical, anarcho-pacifist, Christian worldview that explicitly rejected both violence and the rule of the state.” 7 Consequently, he gained a group of dedicated followers committed to utilising and preaching his teachings “as a lever by which… it would be possible to ‘turn life around,’ that is to destroy both the state and the church.” 8

The Doukhobors, in the eyes of Tolstoy and his adherents, were an exemplary collective through which to exert influence and conduct social experiments grounded in their shared ideals.

BURNING OF ARMS

While in exile, Verigin, inspired by the writings of Leo Tolstoy, exchanged letters with his community. In his letters, he implored them to embrace a vegetarian lifestyle and renounce the vices of smoking and drinking. Most notable of all was his instruction to “abstain from oath-taking,… military duty,… and to destroy all their arms.” 9

In June 1895, Doukhobors gathered simultaneously across the provinces of Kars, Elizavetpol, and Tiflis. In accordance with Verigin’s instructions, they set ablaze every weapon they possessed, signifying their renunciation of violence and their unwavering dedication to peace. This moment would forever be remembered as the ceremonial Burning of Arms, considered by many to be the “first pacifist protest in modern times.” 5

However, this courageous act did not come without its share of challenges. As the fires burned, clashes erupted between Doukhobors and government forces. In the Tiflis District, two battalions of infantry, along with 200 Cossacks, descended upon the peaceful Doukhobors. Unrestrained, they beat and battered them, leaving them bloodied and bruised. 9

IMMIGRATION TO CANADA

After the ceremonial Burning of Arms, the Doukhobors faced a bleak reality. Their villages were placed under martial law, and their once-thriving communities were left in ruins.

“The soldiers were given the right to use the property of the inhabitants, and to behave in their homes, just as in a conquered country. The Cossacks behaved outrageously, and many violations of women occurred. Then the Doukhobors were expelled from their villages. They would be given three days’ notice to clear out, and at the end of the time their property would be sold for a mere bagatelle, and what was not sold was thrown away. The cattle were left to roam and the corn to rot in the fields. The whole population was absolutely ruined.” 9

The London Times, moved by their plight and Tolstoy’s endorsement, brought attention to their persecution. The Quakers in England and the followers of Tolstoy, deeply touched by their cause, began to consider liberating the Doukhobors from the land in which they had suffered so much hardship. 9 Negotiations ensued, and eventually, in 1898, the Doukhobors were granted permission to leave Russia under the agreement that they would never return. 10

The Quakers in London formed a committee to assist with the Doukhobors’ immigration, collaborating with Tolstoy and other sympathizers to raise funds and find a suitable settlement location. The Canadian government, having recently enforced sovereignty over the prairies and its Indigenous population, was eager to find suitable settlers and welcomed the Doukhobors with open arms. Eventually, a guarantee fund of $80,000 was raised, enabling 7,500 Doukhobors to make the journey to Canada.

“Promised a land of freedom, where their religious observances would go unhindered, the Doukhobors set their sights on a new beginning. However, the extent to which their expectations would be met and the challenges they would face in their adopted country remained to be seen. Their entry into this new phase of history was marked by a mixture of hope, uncertainty, and the need to understand their beliefs and convictions.” 11

View of Gibraltar from S.S. LAKE HURON, the ship bringing the first group of Doukhobors to Canada.

INITIAL YEARS IN CANADA

In January 1899, two steamers, The Lake Huron and Lake Superior, delivered the first groups of Doukhobors to Canada. Their arrival was “a scene never to be forgotten.” 13 “Singing psalms of thanksgiving to Almighty God,” they “sailed into Halifax… thankful for their safe transportation over the mighty waters of the Atlantic” and grateful to be free from the country in which they had suffered so much persecution. 12

Both the Lake Huron and Lake Superior made two trips that year, bringing approximately 7,500 Doukhobors to Canada. Among those who accompanied the Doukhobors were prominent Tolstoyans figures such as Leopold Soulerzhítsky, Tolstoy’s personal delegate, Count Sergius Tolstoy, Leo Tolstoy’s second son, Prince Khilkov, a “conscience-stricken nobleman who had given up his fortune and privileges to serve the cause of the people,” and Aylmer Maude, “the English carpet dealer who acquired fame as Tolstoy’s leading translator into English.” 13 The boats also brought several other Russian helpers, including doctors and nurses, who provided their assistance to ensure the well-being of the Doukhobors during the challenging voyage and their early years in Canada. 14

Once the first groups of Doukhobors had arrived on Canadian soil, they embarked on trains to immigration halls in Yorkton, Selkirk, Winnipeg, Brandon and Prince Albert, where the majority would spend their first winter.15

As the snow melted, the Doukhobors trekked to their final destination — three land allotments accounting for nearly 750,000 acres of land in what is now Saskatchewan. Their endowment consisted of three sections: The North Colony, also known as the Thunder Hill Colony, The South Colony, and the Prince Albert Colony, also called the Saskatchewan Colony.15

With the arrival of spring, they wasted no time establishing their settlements, labouring tirelessly to construct humble abodes and cultivate the land. In the first year alone, they constructed “fifty-seven Old World villages,” characterized by a single road down the centre with a row of houses lining each side.15

The Village of Vosnesenya in the Thunder Hill Colony.

The women shouldered the weight of the tasks. They felled trees to build houses, tended to crops, and seamlessly juggled the responsibilities of caring for children, cooking and cleaning. Cultivating the land was back-breaking work. Without money for livestock, the Doukhobor women would strap themselves to the plough, tilling the land with the strength of their bodies alone.

Doukhobor women breaking the prairie sod by pulling a plough themselves. Thunder Hill Colony, 1899.

Meanwhile, the men ventured off to work on the railroads, toiling to earn much-needed funds for their community. Every penny earned “found its way to a common fund and speedily became available for the benefit of the whole.” 16

Despite their hard work, the initial winter proved to be a daunting trial for the Doukhobors. It was particularly challenging for the last group who arrived on the Lake Huron in June and had insufficient time to grow food or construct sturdy dwellings capable of withstanding the Prairie winters. Luckily, The Society of Friends came to their rescue, providing them with food, tools and livestock necessary to withstand that first year. 16

With the fear of persecution left behind, the Doukhobor communities in Canada swiftly earned a reputation for their cheerfulness, and “whether at work or resting in the home, they were constantly singing or chanting their psalms.” 16

A FRACTURING COMMUNITY AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF 1902

While the Doukhobors effectively employed communal labour to survive those first years, conflicts within the community began to emerge. In a foreign country devoid of their spiritual leader, the Doukhobors faced the daunting question of how best to be a Doukhobor in Canada. No longer united in their opposition to the Tsar or Church, they faced the lure of individual freedom as well as the influence of Tolstoyans who were eager to propagate their ideas of true Christian living among them.

Consequently, three distinct groups began to form. Firstly, came those who were enticed by individuality to take up homesteads and abide by all Canadian laws. This group would eventually be known as the Independent Doukhobors.

Secondly, came those who took “Verígin’s interpretation of Tolstoy’s interpretation of the teaching attributed to Christ as representing “God’s truth.” 17 However, “they did not quite shut their eyes to all the lessons of experience and… wished their labour to be productive, their relations with their neighbours to be harmonious, and the order of their lives to be definite and settled.” 17 This group would become known as the Orthodox or Communal Doukhobors.

Lastly, came those who were determined to embody the “Christian Life” and dutifully carry out what they perceived to be God’s work. They believed that “if the “new life” and the “law of God” proved unworkable,” it was only “because they had not carried it far enough.” 17 This group would become known as the Freedomites or Sons of Freedom.

One primary conflict between these groups and eventually with the government was the issue of land ownership. While the Independent Doukhobors felt nothing was wrong with acquiring land individually, the Communal Doukhobors and Sons of Freedom saw private land ownership as conflicting with the will of God.

It is important to note, however, that this idea was thrust upon them by the persuasive influence of Leo Tolstoy. After hearing that the Doukhobors were considering dividing up their land individually, he sent them an extensive letter in which he attempted to convince them to reject private land ownership. A piece of this letter has been reproduced below:

“It only seems as if it were possible to be a Christian and yet to have property and withhold it from others, but, really, this is impossible… At first, it seems as if there were no contradiction between the renunciation of violence and refusal of military service on the one hand and the recognition of private property on the other…. But this is not true. In reality, property means that what I consider mine, I not only will not give to whoever wishes to take it but will defend from him. And to defend from another what I consider mine is only possible by violence; that is (in case of need) by a struggle, a fight, or even by murder. Were it not for this violence, and these murders, no one would be able to hold property.” 18

While Tolstoy’s letter was undoubtedly influential, a Tolstoyan, A.M. Bodyansky, was a key player in promoting this anti-property perspective. Bodyansky came to live among the Doukhobors in Canada after being released from exile in Russia for spreading Tolstoyan propaganda and became a known provocateur of the Freedomite movement. It was “among the Doukhobors” that “Bodyansky found his opportunity.” 19 “As a ventriloquist sometimes uses a big doll with a movable head, so he used the sect as a dummy which served to attract attention to the principles he put into its mouth.” 19

Alongside preaching anti-government and anti-property beliefs among the Doukhobors and speaking on their behalf to the government, Bodyansky may have been a player in spreading a letter from Verigin that exacerbated the division between the Sons of Freedom and the rest of the Doukhobor community. 8

While in exile, Verigin sent two letters to fellow comrades in which he philosophized on true Christian living. These letters were reproduced and distributed among the Doukhobor community. Unfortunately, these letters were musings, not literal instructions, and when received by the Sons of Freedom, were taken as the new Gospel.

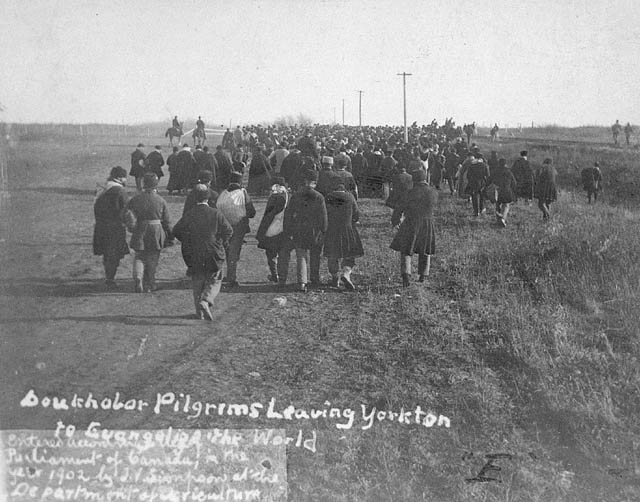

The dissemination of this letter, combined with the growing fracturing of the Doukhobor community, led to the notorious Doukhobor pilgrimage of 1902. Inspired by Verigin’s pondering about the morality of keeping cattle, the Sons of Freedom “let their horses and cattle go free” and gave “their money to the nearest agent of the Immigration Department.” 20 Ridding themselves of all leather and metal possessions, they embarked on a Pilgrimage which “gathering volume like a snow-ball as they passed from village to village, soon reached proportions that alarmed the authorities.” 21

Their intention was “to meet Christ, to preach the Gospel (some of them already spoke a little broken English)” and “to reach a warm country where there would be no Government” and where they could live off of fruit. 20 Again, this was all in strict adherence to Verigin’s writing. In his letters, he stated that “in order to be true followers of Christ, it is chiefly necessary to go and preach the Gospel of truth.” 22 He wrote that “the nearer we individually may be to the sun, the better it will be in all respects” and that ideally, everyone would be fed “on food that grows, and as far as possible, on fruits.” 22

Doukhobors pilgrims leaving Yorkton to evangelize the world.

These Freedomities marched in harsh winter conditions for about 30 to 40 miles to Yorkton, where the women and children were detained and cared for by the authorities and local residents. Meanwhile, the men continued their march to Winnipeg, reaching as far as Minnedosa, Manitoba, approximately 150 miles away, before being brought back by a special train and returned to their homes. 23

PETER VERIGIN COMES TO CANADA

During this entire time, Peter Verigin was in exile in Siberia and guided his community through letters. However, in the fall of 1902, he was granted permission to leave Russia.

Upon arriving in Canada, his foremost endeavour was to counsel the Freedomites, urging them to compose themselves. He told them that freeing their farm animals was unnecessary and that the relationship between animals and humans should be symbiotic.

Verigin also faced the need to deal with the issue of land registration. With Tolstoy’s anti-individual-property beliefs rooted in the community, he faced the imminent task of securing land for his people without conflicting with their morality. While the land had been reserved for the Doukhobors under the Hamlet Clause, it still needed to be entered under someone’s name. Verigin quickly saw that land registration was a mere legality, and, in 1903, he and two other Doukhobors registered all the Doukhobor land under their names. 15

MIGRATION TO INTERIOR B.C.

Unfortunately, in 1906, Frank Oliver, the new minister of the Interior, overruled the Hamlet Clause, which permitted communal settlement and pushed the Homestead Act. The Hamlet Clause had “allowed communal-minded settlers to live in a village within three miles (4.83 km) of the homestead quarter section (160 acres, or 64.8 ha) instead of living on each quarter.” 15 However, Oliver now insisted that the Doukhobors register and reside on individual quarter-acre homesteads, each tasked with farming their own land.

The Doukhobors, who desired to live communally per their religious beliefs, considered the government’s insistence on individual land ownership as a breach of faith. On the other hand, the government believed that the Doukhobors should align with the laws and expectations applicable to all Canadian citizens and became “intent on populating the frontier with independent, owner-occupant farmers.” 13

Ultimately, this conflict resulted in “some 2,500 homesteads, representing approximately 400,000 acres of land” being cancelled, leaving the Doukhobors once again stripped of all they possessed due to their religious convictions. 15

The Doukhobor land rush in Yorkton: settlers gathered to claim Doukhobor land.

Consequently, Peter Verigin orchestrated the decision to purchase private land in the Kootenay region of B.C., hoping that it would secure their religious freedom once and for all. The more moderate climate enticed the Doukhobors, who longed to engage in fruit growing.

Many stood by his decision, while others decided to leave the community and claim land for themselves in Saskatchewan. The majority of communal Doukhobors and Sons of Freedom came to the Kootenays.

The move to Interior BC represented a chance for the Doukhobors to establish a new community where they could maintain their communal values while also adapting to the changing circumstances and opportunities presented by the region. However, when Peter decided to move the community to the Kootenay region, he was unaware that this decision would displace “the last Indigenous peoples to live on the fertile lands at the confluence of the Kootenay and Columbia rivers – the Sinixt Christian family.” 24

- Vysotsky, “New Materials Earliest History Doukhobor Sect.”

- Doukhobor Life in Canada, “Episode 1: Origins in Russia.”

- Herzen, “Novgorod Doukhobor Elder.”

- Blakemore, Royal Commission, 9.

- Rak and Woodcock, “Doukhobors.”

- Blakemore, Royal Commission, 11.

- Thought Co, “Biography of Leo Tolstoy.”

- Inikova, “Leo Tolstoy’s Teachings and the Sons of Freedom.”

- Blakemore, Royal Commission, 14.

- Blakemore, Royal Commission, 16.

- Blakemore, Royal Commission, 17.

- Tolstoy, Christian martyrdom in Russia, 73-74.

- Woodcock, Spirit Wrestlers, 97.

- Adelman, “Early Doukhobor Experience.”

- Tarasoff, “Doukhobor Settlement.”

- Blakemore, Royal Commission, 20.

- Maude, A Peculiar People, 203.

- Maude, A Peculiar People, 271 – 272.

- Maude, A Peculiar People, 213.

- Maude, A Peculiar People, 216.

- Maude, A Peculiar People, 217.

- Maude, A Peculiar People, 224 – 225.

- Blakemore, Royal Commission, 22.

- Wilkinson, “Doukhobor-Sinixt Relations.”