After an active and sometimes perilous career on the North West Frontier, the prospect of a tedious retirement in England did not appeal to the Kemballs, who were still relatively young (Arnold a fit forty-nine, and Vivi only thirty-five). Even less appealing was a descent from oriental luxury in one of the world’s most benign climates, surrounded by an army of servants, to a modest residence in dreary, rain-sodden Kent where a respectable social position would have to be maintained on a Colonel’s modest pension. In this they were not alone.

Inspired by the novels of Rudyard Kipling, Rider Hagaard, and John Buchan, as well as dreams of adventure and prosperity, thousands of English men and women were flocking to South Africa, Kenya, Australia, Canada and other outposts of Empire, the poor to work in mines and farms, their wealthier cousins, “remittance men” and retired military officers like Kemball, to establish ranches and plantations. In 1910, one of the more exotic locales was the Kootenay District of British Columbia, whose cherries, apples and berries were winning prizes across Canada and even at fairs in London.

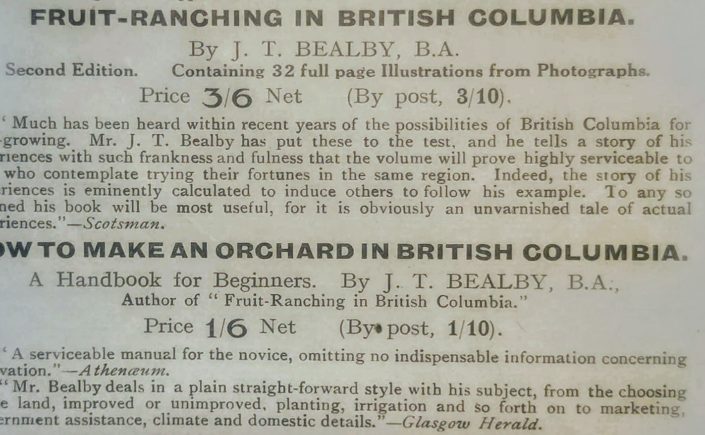

Quite probably it was not a novel but a non-fiction work that inspired the Kemballs. Fruit Ranching In British Columbia by John Thomas Bealby ** was a how-to book, a travel adventure, and a sales catalogue all in one. Published in 1909 in North America, England, Australia, and India, it may well have found its way even to far away Abbottabad where the Kemballs might have come across it while conducting their post-retirement research.

Two Bealby books which were no doubt in the Kemballs’ library

** Bealby’s book is available on line at https://gutenberg.ca/ebooks/bealbyjt-fruitranchinginbc

Bealby, an English gentleman, was a Cambridge educated author who settled in Nelson in 1907. He began clearing land west of the city and then purchased a prosperous farm with almost six hundred fruit trees a few miles to the east. Thus with years of back breaking toil already behind him and in possession of some of the best land in the area, Bealby was able to paint a very rosy picture of the splendours and profitability of Kootenay agriculture.

Even at this early date, the best available land close to Nelson and along the shores of Kootenay Lake and the West Arm had already been developed and what remained was quickly snapped up. After that, the pickings were much slimmer. As the land rose steeply up the sides of the valley, it became rockier and drier. Furthermore, during the previous two decades, prospectors had burned off the trees, scorching the thin soil and causing much of it to erode into the lake below. Before fruit trees could be planted, the charred stumps had to be removed, an irrigation system put in place, and the soil painstakingly replenished. Many an enthusiastic purchaser with Bealby-coloured dreams had a rude awakening – including the Kemballs. Writing a memoir years later, their daughter Gerda Jukes (nee Kemball) described her parents’ first encounter with Kootenay real estate.

The Kootenay District of British Columbia, then highly touted as a suitable area for those wishing to break new ground, seemed highly suited to father’s tastes. He purchased sight unseen from a realty firm in Nelson, B.C. some wilderness property in Crawford Bay described as being “adapted to orchard development.’ Early in 1910 father and mother arrived in Nelson, outfitted themselves with tenting equipment, hired a Chinaman to assist in clearing the property, and set out on the steamer for Crawford Bay.

Only by curtesy could father’s property be considered ‘in Crawford Bay’ since it was located at least two miles from the lakeshore on a bench singularly devoid of water. The Chinaman took one look at the trees, rocks and underbrush which covered the acreage and announced tersely, ‘I quit; I go,’ whereupon he departed. Father and mother were made of sterner stuff, however. They pitched their tent and had their first go at shifting for themselves. As my father became familiar with the area, he realized that the lack of water doomed his land as an orchard prospect. He and mother booked passage for England, but before departing, father contacted Mr. Alfred J. Curle, a land developer in Kaslo, and advised him that my Uncle Jack, due for leave from the army in India, would be coming out within the year to the Kootenay in search of suitable orchard land for retirement purposes…”

Between them, Arnold’s younger brother Jack and Mr. Curle, settled on two lakeshore properties located at the far end of Shutty Bench about five miles north of Kaslo and watered by two creeks – Crystal and Falls (now Kemball). Before returning to duty in India, Uncle Jack….

contracted with the neighbouring Guthrie brothers for the building of two lakeshore shacks on the properties, one of which was to house our family, and the second the hired help which father hoped to bring out for us to assist in the land development.

Meanwhile, back in England, the Kemballs were preparing themselves for their new lives, Arnold with training in the basics of agriculture and irrigation engineering, and Vivi by taking cooking lessons. Upon hearing of Uncle Jack’s purchases, they hired a Norwegian couple as servants who were to join them the next year, and set out for Canada a second time. The following is Gerda’s continued account of the next three years, augmented by two letter written by Col. Kemball to his parents in April and July of 1912.

No amount of schooling could likely have equipped the four of us to cope with the type of life which faced us the moment our feet left the foot plank of the KOKANEE and led us up the small clearing.

We were immediately thrust into a most primitive life style- sleeping on rough bunks, dipping water from the nearby creek and cooking on a converted kerosene tin. Mother’s lessons in haute cuisine did not impair her adaptability unduly, and she began to cope with admirable celerity; allowing herself the luxury of an occasional ‘good weep’ at the end of a particularly back-breaking day. Dorothy and I, innate ‘tomboys’ both and gifted with good health and spirits, took immediately to life in the backwoods. My father, a born craftsman and woodsman, settled right down to the task of clearing land, using a horse and chain pulleys as well as powder when things got particularly tough. Let it not be thought that we abandoned amenities entirely, however. Father always donned a dark suit, and mother a suitable afternoon dress, for dinner, while Dorothy and I appeared at the dinner table garbed in tussore smocks.

We made tremendous strides in 1911. By December, with the help of Haugen and Adriana, the Norwegian couple who had followed us out, we were looking after pigs and chickens, some land had been cleared, and thanks to the efforts of a dear old Scot, Lachy MacLean and the two Guthrie boys, the exterior of a spacious house had been completed. The beaver board required to line the interior walls, however, had gone astray, as had also our furniture which by now had been months in transit.

As the winter days shortened, my mother decided that we should have some proper Scandinavian festivities at Christmas time to dispel our feelings of isolation. Father was accordingly ‘despatched’ to Kaslo in our small, one-cylinder open-air launch, christened GURKHA, with invitations to Mr. & Mrs. James Anderson, Mr. & Mrs. Treby Heal and Major and Mrs. Stubbs of Kaslo and to Bill and Maitland Harrison from Queens Bay to come up to our ranch the day before Christmas and stay overnight. Dorothy and I were given a brief holiday lesson from our daily school lessons which father had been conducting diligently, and all efforts were bent towards readying our rustic surroundings for the festive season.

Three days before Christmas, the KOKANEE made an unscheduled call at our beach, and to our absolute amazement, mother’s older married sister, Mrs. Jakhelen, walked down the footplank. As one of a lifelong series of futile measures to cure her husband of alcoholism, our Tante Agnes had set out from Norway with him to try homesteading on the Canadian prairie. Several months wrestling with nature in the wilds of Alberta having effected no improvement in Uncle’s drinking habits, Tante Agnes had decided that she owed herself a long vacation, so she had packed her bags and caught the train west to the Kootenay District.

Diminutive and zestful, Tante fell in enthusiastically with our plans. I can see her now, ensconced in a snowbank in order to combine the mixings for the festive mayonnaise at the proper temperature. Tante Agnes and her husband eventually went back to Norway, where they settled on a fox and mink farm near Elverun. During World War II, the farm was occupied by some German Army officers, but it took more than an effusion of German brass to flurry Tante Agnes. Mistress of her house and farm she remained throughout the occupation, and she survived to enjoy a number of prosperous post-World War II years, as she was a gifted manager, and had developed one of the outstanding fur farms in Norway. She died in 1972 at the age of 99 years, 4 months.

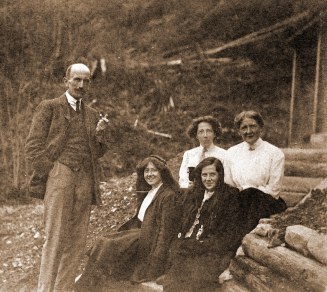

The Kemball Family (including Tante Agnes) at their homestead on Shutty Bench circa 1914

Our Kaslo and Queens Bay guests arrived by launch the morning before Christmas eve, but the day was to bring even more excitement. Shortly after noon, the steamer KOKANEE made another unscheduled call at our beach, ran out the gangplank, and as we watched, stunned with surprise, our household furniture and furnishings, neatly stowed in packing cases, were trundled down on to the snow-covered sand. A wild scramble then ensued as guests and hosts alike pitched in to haul the cases up to our half-finished house. Carpets were laid, chairs and beds made up for our guests. Our Christmas eve celebration was truly one of the high points of my life!

Col. Kemball takes up the tale in a letter dated April 10, 1912

We are very busy now clearing land and building. Haugen and I have just finished quite a smart stable and shed- it really is as good as a carpenter could have done but I will confess it took us rather longer as neither of us had ever put up a building before and a certain amount of time was spent in settling how difficulties were to be met.

We have had only one snow storm I think since the early part of February, so we have been at work outside for the last two months burning up the large piles of brush about the place. I have got one-half the land very nearly completely burnt- which is long and very dirty work. The brush is first cut (slashed) and trees felled. This has to dry out and then with luck one gets a running fire, that is, the whole thing is set fire to. If one gets a good running fire it saves a lot of work, as all the small stuff up to two inches thick is burnt up and one has therefore less to do in the way of picking up and piling afterwards. After the fire one has to pile, sawing the big logs up so that they can be moved to heaps. There is a good deal of art in piling as unless the logs are practically touching the fire burns out and one has to pile again. We are getting more knowing every time. Of course it is very dirty work as the charcoal dust works through to the skin and one is as black under one’s clothes as one’s hands and face are. However it is clean dirt and there is lots of water. I like the work immensely, particularly the axe work, but I confess I am a bit sick of the cross-cut saw on a big gummy log over 2-foot thick – it makes us puff and blow. I have had a Chinaman for a fortnight blowing stumps and some more land ready for him. On the 1st May the teamster comes with his horses to pull out the remains of the stumps and to plough. The land will then be sown to vetch which will be plowed in next spring just before planting. Cherries are a bit of a gamble, everything will depend on what labour one can get after 4 years to do the picking, but I believe I can get pickers from the States, and if I do I shall make a pile. Our cherries are at present only grown in a small way but are a specialty- coming on after all others and being extraordinarily large and well-flavoured. They sell now for 20 to 40 cents a pound and there seems to be a great demand for them. A 3- years old tree bears 40 lbs. of fruit, 8$ worth, so with 100 trees to the acre there is something to be got out of it pretty soon. I think it is worth having a shot at, particularly as most people funk the picking troubles, but if I can once get hold of a good gang of pickers I would make it worth their while to come every year and every year to bring more of their friends until the orchard is in full bearing. It will then be a big job and require considerable organization. Anyhow, whether it turns out the big thing I hope or not I don’t see how I can lose over it and it is very interesting having something to try and work up to.

We have been very fortunate in our Norwegian couple. Vivi likes the woman and I am entirely satisfied with the man who works like a horse. He never talks at his work unless spoken to but always looks pleased and really likes working so he is very easy to get on with. He is learning English quite fast though how he does it beats me as we talk very little, but I imagine he studies the dictionary in the evening, as he comes out with words he has not heard from any of us. The children seem to be quite happy and interested in the chickens. These have paid us just $2 a bird in the 10 months we have had them, not counting what it cost to buy them, but that was roughly half-a-dollar a head. We have been very lucky with them so far and have only lost one the whole time but I put down our success to the fact that we are on virgin soil and our troubles will possibly come later. I am now handing the fowls over to the children, making them up to 100 stock hens as I make out that 25 will supply the needs of the house and after doing that the children can take the profit for pocket money which ought to be a good thing if they manage decently.

So far all is going as well as possible with us and better than I expected. I don’t think any of us regret having come out- the others say they don’t, and I am quite sure I would not change back to India for any thing they liked to offer me. If everything turns out quite well as I hope for in 6 years time the ranch ought to be bringing in £ 2, 000 a year profit, but I don’t really suppose it will, only it might! The winter is not what I expected, for one thing it is only cold for a short time at a spell, we have a week or so of cold bright weather and then a fortnight of dull weather (not heavy clouds) when the thermometer is about freezing point or generally above in the day time.

And a second letter dated July 19, 1912.

We have had the usual ‘most unusual year’ – a very dry spring and then lots of rain at a time when fine weather is generally counted on. The strawberry folk have therefore had a bad year and the cherries have been rather a failure for the first time in twenty years. I hope it won’t keep doing it as I have made up my mind to plant cherries this autumn. We are busy clearing land this summer- it is a slow and expensive business- I don’t wonder at people losing heart over it. It is almost impossible to get labour this year at $3 a day there is so much government road work going on and the sawmills which generally don’t do much in the summer are all working full time so no one can get enough hands…”

The government horticulturist for the district is coming to stay with us next week. I believe his is a good man so his visit ought to be interesting. Very few people from England have come to these parts this year. I fancy that this is due to the extensive advertising done by the big companies which own large tracts of land in the other valleys. I am told that much of that is valueless for fruit growing and if so the buyers will have reason to sorrow for buying land in England without seeing more than the advertisements…”

The children have taken to shooting with a small riffle and are now quite good shots. We are troubled with gophers (a sort of marmot I think) and squirrels which come after the chicken food and vegetables and do a lot of damage generally.. I expect we will be bothered by the deer when the trees are planted. There are quite a lot of deer about but at present there is nothing for them to damage. Vivi has been very busy making jam and bottling cherries. We get through an extraordinary amount, far more than we would have in England. We had the after-effects of the eruption in Alaska for several days the air was full of dust which was very disagreeable as it was quite acid and gave one a sore throat. In some places it destroyed cottons hung up after washing which became quite rotten, however we did not get it bad enough for that here.

Gerda resumes her narrative.

Most of our days in 1912 were spent in splendid isolation, toiling away to prepare our land for orchard development. Father’s preparatory work in Kent during the winter of 1910-1911 began to stand him in good stead, for the flume works which he constructed proved to be a highly effective irrigation system. All of our time cannot have been devoted to purposeful toil, however, for the summer brought us Uncle Jack Kemball, out on short leave from India. I can clearly recall the marvelous fly-fishing which we had at the mouths of our two mountain streams, Falls and Crystal Creeks, and Uncle Jack’s superlative fishing skill which he had perfected in India. A hitherto confirmed bachelor. Uncle Jack also found time that summer to fall deeply in love with a beautiful young girl whose parents ranched on the West Arm of Kootenay Lake. Neither this love affair nor his love affair with his Kootenay Lake property was ever brought to fruition, for Uncle Jack was fated to die of an illness in India before he was due for retirement.**

For the first couple of years we concentrated on growing berry crops. On some occasions we would cram our little ‘put-put’ launch full of crated berries and meander down the lakeshore to the express office in Kaslo. Our faithful launch GURKHA also served us for picnics and for the occasional shopping expedition into Kaslo. When we had to venture further afield, such as to Spokane, Washington for dental treatment, we caught the steamer KOKANEE which passed by on her way to Lardeau three times a week and at least once a week called in at our beach. The arrival of this trim little Canadian Pacific Railway sternwheeler was always an event. Even our two huge pigs would look forward to ‘boat day’ and at the sound of the KOKANEE’s tuneful whistle would come tumbling down the beach to get in the way of the traffic. Mother was a faithful mail-order customer of London’s Army & Navy store, so that the steamer whistle always held the prospect of an eagerly-awaited Army & Navy order.

Dorothy and I rarely saw children our own age, but we did on occasion have some interesting outings. The Andersons took us once on a horseback riding journey up the wagon road to the Ruth Mine at Cody. I recall also an excursion which we made up to the Howser on Duncan Lake where Henry Hincks and his brothers and a group of other retired army types had established a fruit ranching settlement on the principles enunciated in Shakespeare’s LOVE’S LABOURS LOST. Any Howser resident contemplating matrimony was honour-bound to sell his property and leave the community. It was an idyllic existence these men led on the shores of Duncan Lake, and their community was but one of many in the district which harboured a number of happy-go-lucky Englishmen revelling in the life on the frontier. World War I largely put an end to this sort of carefree life, as it ended also the structured sort of life in Britain from which they had escaped.

The months sped by on our lakeshore hideaway. Winters were given over to studies with father and to strenuous winter sports such as skiing and tobogganing. Skiing was a relatively novel sport in pre-World War I British Columbia, but our Norwegian helper, Haugen, was highly skilled at it, and won competitions held in Revelstoke two winters running. Haugen constructed a ski-run down our bench to the lakeshore, and so renowned became his prowess on skis that the steamer KOKANEE on occasion would stand off from shore while passengers and crew would line the rails to watch him carry out his feats of skill on the ski-run.

In the summer months, the hours which could be snatched from physical toil were devoted to swimming, boating, and fly-fishing in our mountain streams. Soon it was the summer of 1914, one of those radiant summers of seemingly endless sunshine. Father completed the planting of our orchard, and we were kept very busy crating boxes of strawberries to Kaslo in our faithful launch. We had an ingenious scheme whereby the packed crates were slid from the bench to lakeshore on a wire. It must have been about this time that the C.P.R. steamer reverted to overnight lay-overs at Kaslo instead of Nelson. The run from Kaslo to Lardeau now became a twice- weekly late night run not too well adapted to the express shipment of soft fruits.

Kemball’s application to re-enlist – 1914

The Declaration of War in August, 1914 struck the Kootenay District like a tornado, uprooting hoards of young Englishmen and Canadians, new arrivals and old, from their lakeshore properties. Father sought to rejoin his Gurkha regiment, but he was unsuccessful in this regard. However, by the spring of 1915 the 54th Kootenay Battalion, C. E. F., had been organized with headquarters at Nelson, and father was appointed Second-in-command. By the middle of June 1915 a full quota of men had been recruited and the battalion was on its way to training in Vernon, B.C.

Mother, Dorothy and I were left to maintain the fruit ranch with whatever casual help might be available, our Norwegian couple having departed some time before. Carry on we did, determined to develop an orchard that father would be proud to return home to. I must pay tribute to the tremendous help which we received at this time from the neighbouring Doukhabor women. In all the years during which mother was left to manage the ranch on her own, we found these Doukhabor women to be honest, faithful, and diligent employees.

At the end of the summer of 1915, Lt-Col Mahlon Davies was posted to raise a pioneer battalion in Eastern Canada, and Father was given command of the 54th battalion, with the rank of Lt-Col. We all participated in some of the formal round of leave-taking which preceded the departure of the 54th for England in November, 1915. Our final parting with father occurred at a tumultuous send-off at Revelstoke, one which I am sure is still recalled poignantly by many a Kootenay old-timer. The festivities over, we went back to the solitude of our lakeshore home to endure one of the heaviest winters of snowfall the District had ever known. We heard frequently from father, who was stationed with his battalion at Bramshott Camp, located near the intersection of the county borders of Hampshire, Surrey, and Sussex in England.

** Jack Kemball survived the war but died in 1921.