Gerda’s memoir tells us very little of the Kemballs’ thoughts and feelings about the war although her matter of fact description of the first few months suggest that there was never any doubt that Arnold would apply for reinstatement. What Vivi and the girls thought about it is unknown but as members of a military family it is probable that they looked upon it as a misfortune which could not be avoided. On the other hand it is also likely that, at least initially, they saw no reason for alarm. Prevailing wisdom had the war over in less than a year, after cooler heads had prevailed and long before the 54th Battalion would be ready for battle. Kemball may even have welcomed the prospect of extra income after the heavy expenses of establishing his ranch.

Initial recruitment for the war was undertaken through the established local militias which contributed the first group of volunteers to the First Contingent of The Canadian Expeditionary Force (C.E.F.) who sailed from Halifax in October 1914. After the fighting over the winter of 1914-15 made it clear that a long war lay ahead, the government began to organize further contingents which were formed into consecutively numbered battalions. The 54th Kootenay Battalion was authorized in May, 1915.

At the outbreak of war, Kemball first applied to his former Gurkha regiment. Not surprisingly, his application was rejected. As the former CO, there was really nowhere to place him in the regimental hierarchy except at the top. Eventually, after an initial posting to the 107th Infantry Regiment of the Canadian Army in Fernie, Kemball was appointed second in command of the 54th and commissioned as a Major. With the departure of the original commander, Lt. Col. Davis, he was promoted to Lt. Col. and led his recruits to a camp for preliminary training at Vernon, BC. In mid-November 1915, following the Revelstoke send-off described by Gerda, they traveled by train to Halifax and then embarked on an eight days voyage to England. At Bramshott Camp on the south coast they underwent more intensive training, specifically geared towards the new reality of trench warfare. Kemball is credited with moulding his raw recruits into a well prepared and cohesive fighting force. He recruited his staff from officers whom he had worked with previously in India. This caused some criticism but was undoubtedly helpful in making it possible to withstand the pressure from high command to break up the 54th in order to replace losses suffered by other battalions. Finally they were assigned to the 4th Canadian Division lead by Major-General David Watson as part of the 11th Brigade under the command of Brigadier General Victor Odlum.**

On the 13th August 1916, the 54th left Southampton and crossed the channel to Havre, France. They were assigned to the Ypres Salient,*** site of the first German gas attacks earlier in the war where the courageous and costly resistance of the Canadian troops held the line and established their reputation as first class troops. After a month of “hands-on” acclimatization in this now relatively quiet sector, they were sent back behind the lines in order to prepare to join the massive assault against the German defenses along the River Somme.

The Battle of the Somme (July 1st to November 18th, 1916) was one of the bloodiest and most futile battles of WW1 in which British and French troops launched a frontal attack against well-entrenched German infantry armed with gas and machine guns. There were 1.2 million dead and wounded on both sides. As part of the British Expeditionary Force, the Canadian Corps had been drawn in division by division since the end of August. In early November it was the turn of the 4th Division.

Canadian soldiers returning from the trenches during the Battle of the Somme (courtesy Library and Archives CanadaPA-000832).

The last assaults of the Somme were attacks on a section of German defenses along the 38 km long Ancre River. These trenchworks were given code names of Regina and Desire. www.canadiansoldiers.com, is an excellent website which gives an overview of various aspects of Canadian military history from 1900 to 2000. The following is its description of the attacks by the Canadian Corps against this sector just prior to the arrival of the 54th Battalion as part of the 4th.

The Canadian Corps was faced with yet another series of attacks on German trench lines, this time a set of entrenchments dubbed Regina Trench by the Canadians. These attacks were to be the most futile and costly of all the Canadian efforts in the Somme fighting. Just two days after the exhausting fighting for the Hessian Trench, the 5th Brigade (2nd Division) and 8th Brigade (3rd Division) once again went into the attack on 1 October. The operation was a disaster, beginning with short-falling artillery plastering the jumping-off positions. The preparatory barrage also failed to hit the German lines, and German wire was not cut by the artillery in most places. Casualties were heavy during the assault as machine gun fire laced into entire assault companies caught up in No Man’s Land. The few survivors that managed to reach Regina Trench were driven out or overwhelmed by German counter-attacks, and half the assault force was dead or wounded by day’s end with no gain to show for their efforts.

A week later, another assault was launched on 8 October 1916, with two brigades of the 1st Division and two more from the 3rd Division, on a reduced front. Only a single battalion of the 3rd Division managed to enter Regina Trench in strength, but were forced out by three counter-attacks. A number of weakened sub-units of the 1st Division reached their objectives but were likewise forced out when they ran out of ammunition. It was during this attack that Piper James Richardson of the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish) performed acts of bravery for which he was later posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. For a cost of 1,364 casualties this day, the Canadian Corps was able to claim no additional territory gained.

A month later the 4th Division, including the 54th, was ordered to undertake one final attempt.

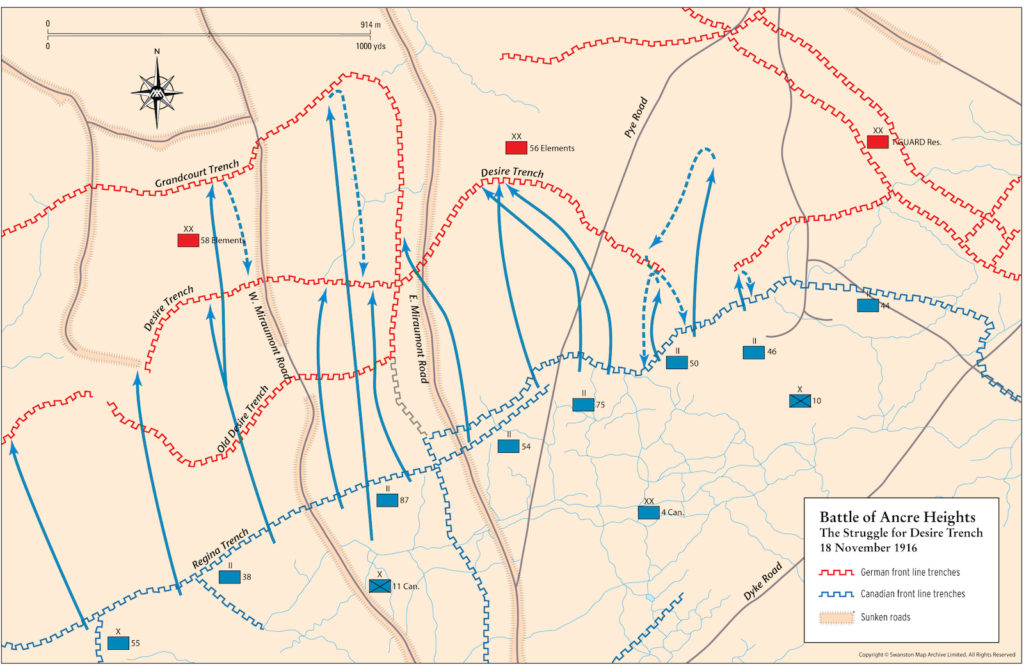

The night of 17-18 November brought the winter’s first snowfall, and the operations began just after 6:00 a.m. on 18 November in a driving sleet that changed to driving rain as the morning progressed. The 4th Division, having taken over positions from the 18th Division’s right-hand brigade on 16 November, attacked on a frontage of 2,200 yards. The infantry was forced to plod through freezing mud, the snow masking objectives and causing units to lose direction. Artillery observers couldn’t spot targets and could only fire their pre-arranged programmes.

The 11th Brigade, on the left, represented the main effort. Reinforced by a battalion of the 12th Brigade, four battalions attacked astride both Miraumont roads (from right to left, 75th, 54th, 87th and 38th) while the 10th Brigade assaulted with the 46th Battalion on the right and 50th on the left, east of the Courcelette-Pys road. Artillery support was again heavy, with four divisional artilleries (1st Canadian, 2nd Canadian, 3rd Canadian and 11th British), 2nd Corps Heavy Artillery and the Yukon Motor Machine Gun Battery all firing in support. No. 2 Special Company Royal Engineers screened the advance with a smoke screen across the front and right flank.

The Canadian task was to seize Desire Support Trench and establish a new line 100-150 yards beyond, exploiting farther if possible. (A late order issued by General Watson’s headquarters at 2:30 a.m. directed the 11th Brigade to advance to Grandcourt Trench, some 500 yards beyond Desire Support.) At zero hour, while maintaining a concentrated standing barrage on the enemy trenches, the guns put down a creeping barrage, behind which the infantry companies (two from each battalion except the 46th) advanced in four waves at intervals of 50 yards or less. Fine coordination between artillery and infantry brought excellent results. In less than an hour the 54th Battalion had sent back its first group of prisoners. By eight o’clock both brigades had gained their initial objectives and were hastily digging in beyond Desire Support. Prisoners from the 58th Division were coming back in groups of as many as fifty at a time. A German counter-attack against the 54th Battalion ended suddenly as the enemy threw down their weapons and surrendered; a second threat was broken up by artillery fire. On the left the 38th and 87th Battalions, having overrun both Desire and Desire Support, pushed strong patrols down the slope to Grandcourt Trench, establishing machine-gun posts there and taking more prisoners. The day’s total harvest by the 4th Canadian Division was 17 officers and 608 other ranks.

A map of the attack on Desire Trench.

Unfortunately the success achieved by Brig.-Gen. Odlum’s troops was not matched on either flank. The situation with the 10th Brigade on the right – never as favourable as it seemed – had changed for the worse. The one assault company of the 46th Battalion had suffered so heavily from small-arms fire that it could not hold the ground it had won. On its left the 50th Battalion, having lost touch with the 11th Brigade, was forced back to Regina Trench by heavy machine-gun fire from both flanks. The 18th British Division, too, had been less successful than early reports suggested. The 55th Brigade (on Odlum’s immediate left) seized about 300 yards of the east end of Desire Trench, linking this up with the Canadian-won portion of Desire Support, but the rest of its objective was still in enemy hands. There had been partial success in the valley of the Ancre, where the inner wings of the 2nd and 5th Corps had pushed a salient forward half a mile beyond Beaucourt but General Jacob’s left wing had failed to reach Grandcourt or Baillescourt Farm; and north of the river the 5th Corps had added very little to its gains of 14 November.

Suffering heavy casualties, both corps were no longer in a condition to continue the offensive. The 56th Division’s relief of the 58th during the day indicated a strong likelihood of new counter-attacks against the right wing of the 2nd Corps, and Major-General Watson decided as early as 12:30 p.m. to pull his patrols from Grandcourt Trench in order to shell as preparation for a full-scale assault. At 7:50 p.m., the situation across the Army front caused the cancellation of all further advance orders by the British 18th and 4th Canadian Divisions. The positions in Grandcourt Trench were most likely untenable in any event, but the gains of the day had been considerable – a half mile advance on a 2,000 yard front, for the loss of 1,250 casualties while inflicting heavy losses in killed, wounded and prisoners. In any event, heavy rain on 19 November prevented any further attacks regardless of the ability of the British corps to continue, and the 4th Canadian Division had at last fought its final battle on the Somme.

Aftermath

Distinguished Service Order medal – awarded to Kemball following the successful capture of Desire Trench, November 1916

The 4th and 5th Army was faced with the task of preparing for winter. Fresh divisions had to be found for the front, where communications and front line trenches had to be repaired and strengthened. The 4th Army extended its front over four miles of French front, moving the boundary from Le Transloy to within four miles of Peronne, freeing three French corps for the spring offensive the French were preparing. The 4th Canadian Division remained in place, having spent seven weeks continuously in the front line before handing over to the 51st (Highland) Division between 26 and 28 November. The division rejoined the rest of the Canadian Corps on the Lens-Arras front.

Canadian battle casualties at the Somme had totalled 24,029. The Battle Honour “Ancre, 1916” was awarded to units for participation in these actions.

The attack on Desire Trench was spearheaded by the 54th under the command of Lt. Col. Pgiven to officers in actual combat who had distinguished themselves while under fire. It was also generally considered to reflect honour on the soldiers under his command.

The weather, which had been the worst in many years, then prevented further operations and the battalion, after a brief spell behind the lines, was transferred further north as part of the Canadian Corps preparations for the attack on Vimy Ridge.

** That he was initially appointed second in command of the 54th and over the next three years only received that one promotion, despite his success, suggests that the Canadian military and political leaders were determined to reserve the upper ranks for native born officers – which Watson and Odlum, with considerably less active service experience, were.

*** A salient, also known as a bulge, is a battlefield feature that projects into enemy territory. The salient is surrounded by the enemy on multiple sides, making the troops occupying the salient vulnerable. (Also see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salient_(military)