From The Marne To Vimy Ridge

The Western Front, a 400-plus mile stretch of land weaving through France and Belgium from the Swiss border to the North Sea, was the decisive front during the First World War. Whichever side won there – either the Central Powers or the Entente – would be able to claim victory for their respective alliance. Despite the global nature of the conflict, much of the world remembers the First World War through the lens of the Western Front.

The war on the Western Front began on 3 August 1914 with Germany aggressively marching into Belgium and Luxembourg. The next day Britain declared war on Germany, setting the stage for the war on the Western Front. In Belgium, Liège and Namur both fell within a matter of days, opening the way for German armies to invade France [hoping] to sweep around the French left flank, take Paris from behind, and force France to capitulate in a matter of weeks.

Meanwhile, France made its own offensive further south into Alsace and Lorraine [which] met uniformly with disaster. Led by incapable officers, French formations blindly groped their way forward without sufficient reconnaissance…and were ultimately pushed back by more organized German forces. France lost over 300,000 dead in 1914, making it France’s second-most deadly year of the war. The Germans stretched themselves perilously thin chasing after French and British troops in headlong retreat after the initial encounter battles in August.

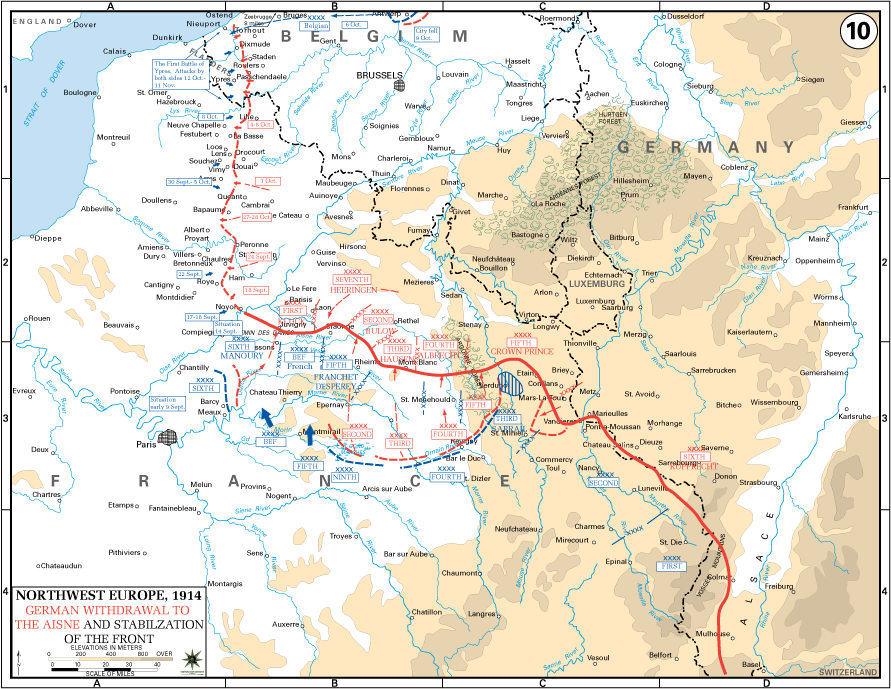

The German plan required a rapid, coordinated sweep that envisioned the First and Second German armies advancing rapidly along the French, British, and Belgian left flank. Covering such a vast area, however, proved to be very difficult logistically and the German armies began to drift apart. The time had come for the Entente forces, which had been rapidly falling back before a seemingly unstoppable German onslaught, to stop and fight. From 5 September 1914, French and British formations fought their way into a gap between the German First and Second Armies, part of a struggle called the Battle of the Marne. Entente and German forces fought over nearly the entire length of the front, making the Marne one of the largest engagements of the war, as well as one of the most important. The Germans had no choice but to retreat, stopping at a line behind Verdun, Soissons, and Reims. When renewed French attacks were halted by the once-more cohesive German forces, Joffre, commander-in-chief of the French army, ordered troops to move to the far left flank and try to outflank the Germans from the north. The effort was repulsed and countered by a German attempt to turn the French flank in turn. The so-called “Race to the Sea” saw both forces make ineffectual attempts to turn the northern flank until they found themselves at the North Sea. With no flanks left to turn, the Western Front as we think of it came into being: a solid front from the sea to the Alps, with only one way through: straight ahead.

There were a few attempts to break through this line before the winter weather set in and exhausted, overstretched units became incapable of action. Trench networks could not be broken by hasty offensives, but rather had to be systematically neutralised by concentrated heavy artillery fire. The armies on the Western Front spent the next four years trying to coordinate ever-more complicated attacks to break trench networks of increasing depth and complexity. It was this rapid and constant innovation, rather than stodgy conservatism, that created the bloody stalemate on the Western Front.

1915 saw a staggering number of battles on the Western Front [which was also] constantly simmering with low-level violence, producing daily casualties that were lumped together with losses due to disease or the environment as mere “wastage”.

In February, The French launched The First Battle of Champagne in many ways [setting] the precedent (and a poor one) for the shape of offensives in 1915. The French managed an acceptable initial advance and then spent a month relentlessly hammering against a solidified German line to no avail. In all, upwards of 200,000 French soldiers were killed or wounded for a modest advance (no more than three kilometres in the most successful sectors); the Germans suffered only 80,000 casualties in defence.

Undaunted, the French continued to launch and maintain such attacks throughout the year, making 1915 the deadliest year for French forces (349,000 deaths). The British, for their part, did not remain idle, but could not commit nearly as many troops as their French ally. They made a series of largely abortive efforts to support larger French battles. The Battle of Neuve Chappelle (10-13 March 1915) stands out as the only truly independent effort. The small-scale battle, whilst initially successful, eventually petered out, with British troops unable to capitalize on their initial gains. This was a long-standing problem in trench warfare: the initial “break in” was not too complicated for well-supplied troops to achieve. Doing anything with that initial break in, however, proved exceedingly difficult. The Germans suffered a similar fate the next month in their attempt to test the trenches on the Western Front.

The Germans instigated one battle on the Western Front in 1915. Rather than hoping that the battle would win some grand strategic victory, the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April–25 May 1915) was largely designed as a testing ground for a new weapon of war: poison gas. German forces had secretly installed a series of chemical tanks across their front line trenches, and on 22 April 1915 released their deadly chlorine gas to waft over to the French and British trenches opposite them. Where the gas fell thickest the Allied lines simply melted away. French African colonial troops fell back in disorganized panic. On their flank, Canadian troops held on doggedly for days, isolated and repeatedly attacked by German forces. Entente forces were able to recover from the momentary collapse due largely to the lack of German effort: unconvinced that the gas would be as effective as it proved, the Germans had no plan in place to exploit any possible breach in the Allied lines. The result after a few weeks was, again, a minor territorial gain of no strategic importance for tens of thousands of casualties.

The German commander, Falkenhayn, knew that he did not have enough forces to pummel the French into submission or to push the British back into the sea. Even if he had, the inherent strength of field fortifications meant that such an effort would be unduly costly for Germany, and perhaps lead to nothing more than a pyrrhic victory. The staggering losses the French suffered in 1915 were well understood by German strategists. It was here that Falkenhayn placed his hopes. If he could force the French to attack with the same ferocity and lack of success as they had in 1915, the French Republic could prove incapable of bearing the burden and be forced to sue for peace. Such a peace would rob Britain of its operating bases in France and likely compel them to sue for peace in their own time. The trick was to put German forces in a position where the French would have no choice but to attack and to continue to attack, whatever the cost. Falkenhayn deduced that the ancient fort of Verdun would be just the spot.[15]

The fort at Verdun had been France’s bulwark against the “Germans” for centuries before either nation existed in its modern form. It was supposedly a national symbol that the French could not let pass into German hands (although this interpretation has become increasingly contentious). Counting on this, Falkenhayn launched his attack on 21 February 1916. This was a strategic offensive that relied on the strength of the tactical defensive. The French and German armies grappled for the next ten months in the longest land battle in history.

From a German perspective the Battle of Verdun had but one purpose: to kill as many French soldiers as possible. This was attrition, conceived in its purest form. The casualties were enormous, although fewer than one might expect from such a battle. Ultimately some 300,000 soldiers from each army were killed or wounded. The battlefield conditions were barbaric. Troops were fed mechanistically into an ever-grinding machine of fire, steel, mud, and death. French troops felt that the battle was a futile waste of lives. They expressed what they felt was the obvious lack of value placed on their lives by bleating like sheep being led to the slaughter as they marched into the Verdun salient; a bone-chilling foreshadowing of the widespread mutinies that would wrack the French army in 1917.

The situation for German forces was hardly better. Whereas French forces were rapidly and aggressively rotated in and out of the front, ensuring that troops did not have to endure more than a few days at the hellish front, German units were frequently left at the front for weeks on end. This horrific treatment severely sapped German morale and fighting power. Nevertheless, the Germans very nearly pushed the French to the breaking point and the French command demanded that a strong offensive be launched elsewhere in order to draw German forces away from their beleaguered troops. That battle became notorious in its own right: the Battle of the Somme.

Verdun was the longest battle on the Western Front in 1916, but the Somme was the bloodiest; it sent nearly twice as many men to their graves in half the time and was in many ways the archetypal Western Front battle.

At 7:30 am on 1 July 1916, some 55,000 French and British troops went over the top in the initial wave of the assault across a sixteen-mile front. Their success was variable. In the southern sector French and British troops advanced rapidly, captured their objectives, and solidified their positions at minimal cost. To the north, British formations were mown down, capturing very little and sustaining heavy casualties. With concentrated machine gun fire, effective pre-sited artillery barrages, and barbed wire emplacements that were frequently still intact, the Germans in the northern part of the battlefield easily repulsed British attacks. The persistent cultural myth of British soldiers slowly walking across No Man’s Land in serried ranks only to be mown down by enemy fire are largely a faint memory of the sad reality some units faced on 1 July 1916 on the Somme. Attacking battalions in front of Serre suffered over 50 percent casualties, an absolute catastrophe. The Royal Newfoundland Regiment lost 91 percent of their forces that day attacking Beaumont Hamel. Secondary waves faced deadly fire before even reaching the British front line. Forced to march over open terrain due to the communication trenches already clogged with the dead and dying, they made easy targets for German artillery and machine guns, which sometimes engaged British infantry at ranges of over half a mile. It is easy to understand why the First World War is seen as futile when recounting incidents like these.

By the end of the day, British forces had suffered 56,882 casualties, including 19,240 dead. Despite gains in the southern sector, the overall result fell crushingly short of success. The French and British continued to attack vigorously through to December. All told the battle claimed around 1.2 million casualties, roughly 600,000 from the German army and a combined 600,000 from the Entente (roughly 400,000 British and 200,000 French). Through this great blood-letting, the British learned hard lessons in modern warfare.

The Somme set the stage for the string of impressive battlefield successes the army achieved in 1917 and 1918. Tanks were first used at Flers-Courcelette on 15 September 1916, forever changing the face of warfare. French troops twice broke through the German lines and for a brief moment found themselves with no immediate obstacles between their position in the fields of Picardy and Berlin. However, these local successes – the result of a relentless, methodical, operational hammering at the German lines – led to nought. If the Allies were to beat Imperial Germany, it was going to have to happen some other way.

1917 was in many ways a desperate year for both the Allies and the Germans. Faced with continued encirclement, a biting blockade and struggling allies, German war-leaders needed to knock at least one of the Great Powers out of the war as quickly as possible to stand any chance of even a conditional, negotiated victory. Hindenburg and Ludendorff chose to continue operations in the theater of war where they had earned their fame: the Eastern Front. To help free up men for the coming offensives, they withdrew forces to the so-called Hindenburg Line. This new line of fortifications both shortened the length of the frontage Germany had to man and was well protected by concrete bunkers and well-planned out defensive arrays. These further economised on manpower and were quite difficult for the Entente powers to break through.

For the Allies, 1917 needed to be better than 1916. The British commander, Haig, wanted more than ever to have a truly independent hand in operations, and he sought to pursue independent battles in the British sector. Before 1917 British battles had been part of broader French efforts and under some level of French strategic direction. Haig got his wish (although not in the way he had hoped. When further advances failed disastrously, French troops mutinied and while continuing to maintain the defensive, refused to attack. As a result the French commander was replaced by Marshal Petain who had an enormous task on his hands and immediately set to work trying to quell the mutiny. He made immediate efforts to organise better food and more frequent leave for the troops. He also cracked down on individuals believed to be “ring-leaders”. This did not, however, end the mutiny over night; it took months before the French were ready for another offensive action. Fearing what would happen if the Germans learned of the French indiscipline, they became desperate for a British attack to ensure that the Germans were preoccupied elsewhere.

For the first time in the war, in 1917 Britain acted as the senior partner on the Western Front. The British launched a series of independent battles in 1917, starting with their attack on Vimy Ridge.