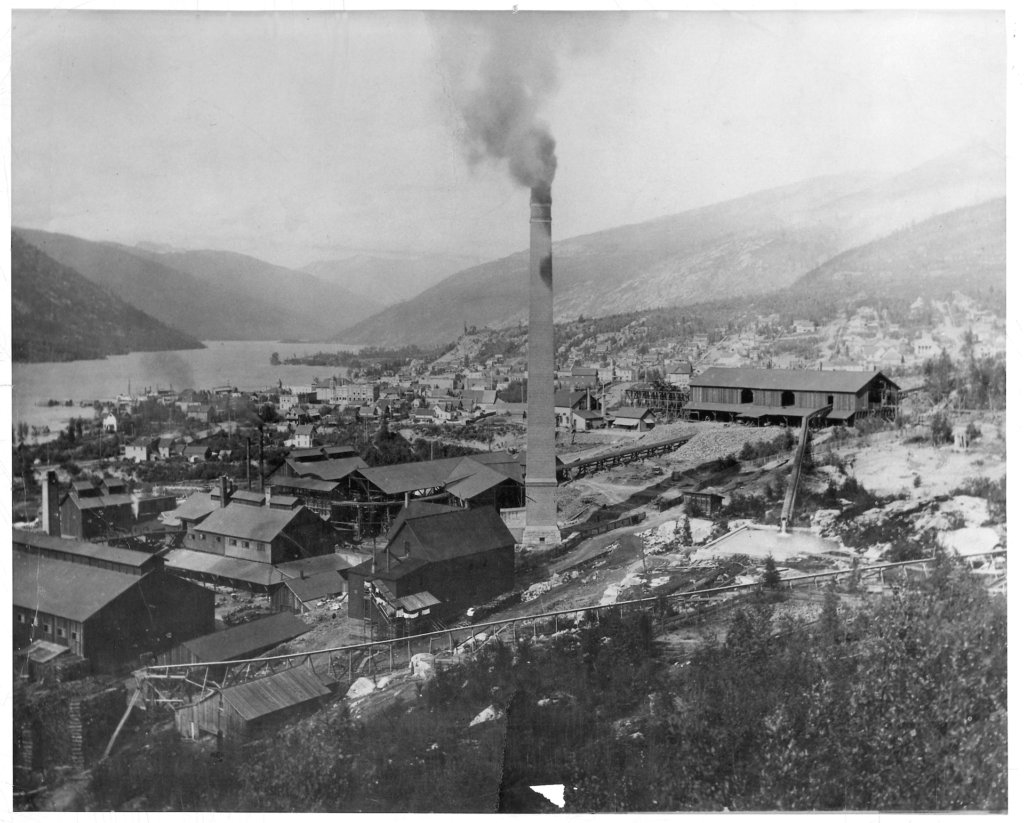

The history of the Consolidated Mining & Smelting Company (Cominco) in Trail starts in 1895 when August Heinze, an American businessman from Montana, built the initial smelter on the west bank of the Columbia river. The first furnace was opened a year later, in 1896, and a narrow gauge railway was constructed to link the smelter to the surrounding mines. In March 1898, Heinze sold the operation to the C.P.R. which subsequently created a separate company to run the smelter. This company evolved into the Consolidated Mining & Smelting Company (Cominco) and is now Teck Resources Ltd.

The smelter was already at this time one of the largest metallurgical works in the world. Seeing the success of the Trail Smelter, the C.P.R purchased several more mines to have their rich ores processed in Trail. They acquired the St. Eugene Mine at Moyie, the Center Star mine in Rossland, and later the Sullivan Mine in Kimberley. The latter proved to be a particularly good purchase, as it had very rich lead and zinc ores, which would be in high demand for the shells of WW1.

Innovation in the handling of the ore from the Sullivan Mine was at the hand of Selwyn Blaylock, who found an innovative method to deal with the complex ore found in Kimberley. In an article by Blaylock in the Nelson Daily News on May 21st, 1917, he states that “The Trail plant today is probably as complete a metallurgical institution as there is on the continent…We are working about 1600 men and we are making electrolytic copper, copper sulphate, electrolytic lead, lead pipe, shrapnel, wire, electrolytic zinc, gold, silver, sulphuric acid, and hydro fluo silicic acid. All of these with the exception of lead, gold and silver have been accomplished since the war started and were caused primarily by the need for the material by the munitions board.” In short, the smelter saw rapid growth as a result of the war, and innovation and new processes for dealing with a wide variety of materials secured the success and livelihood of the smelter. Prior to WW1 in 1914, Canada did not have a smelter capable of treating ore with high levels of zinc. Previously, this ore had to be processed in the States, with high tariffs and challenging logistics.

While the first BC smelters were built as early as 1868, and a total of 24 were built by 1915, only the one in Trail survived. 18 of these pioneer smelters in BC were to return nothing on their initial investment. Only five smelters in the Southern Interior had even temporary success, lasting from 5-19 years, but even these eventually failed due to poor management and technological ineptitude. It required innovative methods and thinking to be able to understand how to best manage the mineral rich ores of the region. The Cominco Smelter, however, “succeeded because of sound management, adaptability, use of its own research, diversification of ores smelted, by ensuring its own supply, by owning its own mines, and by ensuring its own energy supply by owning a hydro-electric operation, and its own coal mines.” (Morrison, 7). It should also be added that a docile and exploited workforce was the true driving force behind these early smelter operations, and that the success of plants such as Cominco was largely because of their workers.

In the early days, fumes from the smelter were a problem and much of Trail was impacted by the terrible air quality. It is said that “Air pollution, primarily sulphuric smoke, was so bad that trees died on the mountainside, residents in the gulch had to cover their gardens with burlap sacks, and children miles away choked and cried. Toxins in the zinc plant forced workers to learn quickly that survival was enhanced by covering their mouths with cotton pads, furnished, of course, at their own expense” (Scott, 60). It was only in 1930 that the company decided to collect the sulphur from the smokestack to be put to use in chemical fertilizers.

Smelter workers lived in over-crowded living conditions in an area known as ‘The Gulch’, down wind from the smelter and inundated with toxic air. Management and executives from Cominco, on the other hand, lived in the nearby residential settlement of Tadanac, enjoying a much more spacious and ventilated environment out of the way of the harmful smoke and with a view of the Columbia River.

History of Workers Rights, Safety & Exploitation in the Early Mines and Smelters of Interior BC

The lived day to day realities of working in the smelter at the Cominco plant were dangerous and largely unregulated with little to no regard of safety or workers rights. In 1911, the wage of a smelter man was $2.75/day, regardless of the hours worked. When workers at the Cominco smelter came into work, they wouldn’t know if they were to work an eight or twelve hour shift. In 1899, British Columbia instated an eight-hour work day for the metal and mining industry, however, companies such as Cominco and the surrounding mines of the Kootenays advocated for this to not be mandatory. In short, the company fought the federal legislation at the expense of their employees in return for higher levels of productivity, even though this decision certainly put workers in even more dangerous situations. No-one was ever sure of continued employment and getting started to work in the smelter often involved bribing the current employees. Sick days, holidays and time off were words foreign to the men working in the smelter. Fear and ease of being replaced drove their acceptance of substandard working conditions. “The influx of people from Europe, the U.S., Latin America, and Asia created a large surplus labour pool and drastically affected union attempts to organize. Not only were the newly arrived immigrants reluctant to involve themselves in union activity for fear of reprisals or deportation for anything that could be interpreted as political activity, but others were faced with the prospect of being fired or blacklisted for joining a union at a time when many were anxious for jobs” (Solski & Smaller , 33).

The underground working conditions in surrounding mines in the Kootenays were dangerous and many men died from lung diseases, dynamite explosions, and rock falls. In the smelter, there was a 160 degree lead furnace, and workers would sometimes catch fire or be subject to lead poisoning. Without protective clothing (only heavy wools), the hand casting of lead and zinc was a much more dangerous task than it needed to be. There were no hard hats or safety glasses and workers were left to their own defences on the work floor of the smelter, leading to dangerous situations with no company accountability for injury. As an early Cominco employee stated when asked about protective clothing: “that’s like asking, did they go for holiday on the moon. No, there was no such thing as hard hats or safety shoes with steel toe caps. Goggles, never even heard of them” (Mayse, 96).

Many smelter-men were immigrants who feared that if they dared to unionize that they may not only be fired, but deported. Fear of striking led immigrants to accept substandard working conditions, as exploitative work was better than no work, and often they did not yet have the political consciousness to understand the conditions of their exploitation. It was through bare material necessity that workers accepted sub-standard working conditions. As one smelter-man said, “We didn’t dare get sick, because someone else would take our jobs” (Scott, 60). It is only through the work of individuals such as Ginger Goodwin spreading information about workers solidarity and collective rights that desires began to stir in workers to band together and press for better representation, pay and safety. People such as Ginger Goodwin were integral to the gradual movement towards fair pay, an 8 hour workday, and safer working conditions in BC as well as across Canada. In short, workers rights in the mines and smelters of the early 20th century in BC were fought for, and not given. Leading up to the strike in 1917, a combination of “impossible working conditions, poor wages, and the obvious discrepancies in town living conditions forced even the most docile employees to question management practices; to many, a union was becoming more and more attractive” (Scott, 61). In sort, the desire to unionize was perhaps felt on individual levels prior to this time, however people such as Ginger Goodwin took steps to actualize the reality of union representation.