Apprenticeship

John Houston left home at the age of fourteen to live with relatives in Chicago and apprentice in a print shop. It is probable that, except for the few years at the height of his political career, printers ink was somewhere on his clothes, under his nails or staining his fingers, for the rest of his life.

After leaving Chicago, he spent the next twenty years criss-crossing the United States, going from one printing or newspaper job to another in New York, Texas, Missouri, Montana, California, Idaho and probably a few more in between. Sometimes he took time off to go prospecting or engage in real estate deals – John was always looking to strike it rich – but before long he was back beside a printing press – as jobbing printer, reporter, or editor. He had a knack for it too – over the years he honed a unique and identifiable prose style – colourful, homey, sharp-tongued, full of humour and personal conviction – a voice that conveyed a strong sense that it spoke the Truth.

Little is known about these years but it is probable that a fierce temper, a refusal to suffer fools with even remote gladness, and an addiction to alcohol, were the reasons behind the constant brevity of his various employments. In support of the temperance movement in The Prince Rupert Empire, his last newspaper, he wrote:

I speak of these matters…. out of bitter experience, as one who has played the game in many new cities and camps, and by his own mistakes lost fortunes, health and the regard of many whose good opinion he most valued.

Settling Down

By the age of thirty-six, however, he at last felt the need to put down roots, to achieve some measure of worldly success. Returning to Canada, he began to look about for the right place to start a newspaper – a town with not much past but with plenty of future. After spending a year working as a reporter for the The Calgary Herald, he borrowed “a handful or two of old type,” moved to Donald, the newly created CPR divisional point, and established the first of his seven newspapers, The Truth.

His years of wandering through the mining camps of the US now stood him in good stead because soon his paper gained a reputation throughout North American mining circles well beyond its obscure location. It wasn’t long, however, before he formed the opinion – quite correctly – that Donald had neither past nor future and in 1889, he moved The Truth to New Westminster, BC’s former capital. Here again he quickly realized that the city’s best days were behind it. But again his mining experience came into play as he turned his gaze towards a town with absolutely no past and a very promising future.

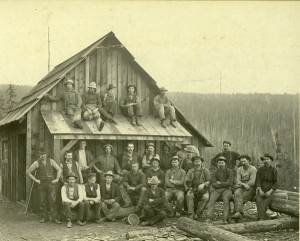

Packing a much improved printing press by rail, steamboat and mule, Houston and his two partners – Charles Ink, an appropriately named printer, and Gessner Allan, a Notary Public – arrived in Nelson in the spring of 1890. By then Houston had acquired the nickname of “Truth” but nonetheless decided to christen his newest paper The Miner making it clear from the start whose side he was on. Putting his paper to work in the service of John Houston the businessman, and later of Houston the politician, he made an immediate impact on the town and soon established himself as a leading citizen.

First and foremost, The Miner was an instrument of Houston’s determination to make Nelson into a thriving and permanent community and thereby to raise himself into a position of power and wealth. In the mining world of boom and bust he knew how important it was to give Nelson those facilities and institutions that would guarantee its prosperity – and to do it before other centres, like Kaslo and Trail, beat it to the punch. He became a tireless promoter of Nelson’s mineral resources, its potential as a transportation hub, a lumber town and a government centre. He recruited the first doctor, helped establish a school, and even published lists of trades and professions the town needed and which would thrive there. He called for better postal service and proposed mining legislation that would ease the way to more capital investment and exploration. He also undertook to raise the moral tone of the city in hopes of attracting permanent families by demanding that the police deal with the “hobos, pimps, and tinhorn gamblers” who naturally flocked to mining camps. And above all, he attacked the CPR for its strangling monopoly on land around the city and its attempt to dominate the real estate market in exchange for granting Nelson terminus status.

The CPR had already exchanged the building of a twenty-eight mile rail line between modern day Castlegar and Nelson for 200,000 acres of government land. A further amendment to this subsidy also granted the company half the townsite, including land which prevented expansion. He accused Premier Robson of “handing [Nelson] over, bag and baggage, to a jerkwater railway” namely the CPR – “the greediest railway company on earth.” To his credit, and no doubt to the credit of other businessmen and politicians, he eventually succeeded in forcing the government and the CPR to put the land up for sale at public auction.

Taking The High Road – Or Not

The extremely forceful eloquence of these attacks, the clarity, humour, and elegance of Houston’s prose style won him praise throughout the northwest. By the spring of 1892 he was considered the region’s most noteworthy journalist and easily the most recognized citizen of Nelson and indeed the Kootenay. It came as quite a shock, therefore, when Houston announced at the end of April, 1892, that he had sold The Miner, stating in an editorial that

In order to conduct a newspaper thoroughly independent in tone, its owners must be in an independent position, and they cannot be in that position if engaged in enterprises the capital for which is supplied by various individuals, all of whom have varied interests – interests that too often clash with the public.

Such high-mindedness was certainly laudable if uncharacteristic of a man whose newspaper had previously been so consistently at the service of his business interests. But so it was – until October of the same year when he announced that he was starting a new paper, The Tribune. Howls of outrage came from the editorial pages of The Miner.

We bought messrs Houston and Ink out of The Miner in the end of April, and paid them cash, not only for the plant of the newspaper, but a fair price for the good will of their business. We bought in good faith and it now appears that mr Houston sold in that same good faith which has characterized all his business dealings in the West Kootenay.

The Miner’s editor went on to say that “the petty and self-seeking” Houston had sold in order to get cash for business ventures which had subsequently failed and so was looking to get back into the newspaper business to recoup his fortunes. He added that Houston had made an offer to repurchase his former paper but on terms so outrageous as to presume “a peculiarly poor opinion of our intelligence.”

Such an explanation is possible but another is perhaps more likely. Given the obvious and growing divisions in Nelson between the miners, working class men and saloon owners who supported Houston and the “better class of men” – professionals, mine managers and other ‘respectable’ citizens – Houston probably realized that the establishment of a second newspaper was inevitable and he might as well get something out of it. The short time between the sale of The Miner and the start up of The Tribune supports this theory. Having sold “the plant of the newspaper,” he would necessarily need to order a new one and await its arrival just six months later. This certainly suggests the strong possibility that Houston, at the time of sale, had already decided that the second paper might as well be his own. It was a nice touch too that The Miner was now the name of the paper of the mine owners, while his own was The Tribune, a name taken from the defenders of the rights of the people against their social superiors in the days of the Roman Republic.

The Tribune carried on Houston’s political and business agenda as if he had never left, its first edition not deigning to answer The Miner’s charges but, no doubt gleefully, publishing a list of its new advertisers, prominent local merchants all. First on that agenda was a petition for the incorporation of Nelson, a cause whose time had not yet come – due at least in part to suspicion that Houston wanted it so that the fledgling city would buy out his struggling Nelson Electric Company. Over the next four years, attacks on the CPR and corruption in Victoria continued, as did promotion of Nelson real estate and mineral potential while Houston continued to pursue his various ventures. And all the while, despite occasional economic downturns, the town continued to grow and prosper.

In 1895 the lure of gold took Houston to Rossland where he established The Rossland Miner which he attempted to run as a commuter, travelling back and forth on a weekly basis. He soon tired of this, however, and contented himself with promoting his real estate holdings at a distance. He sold the paper, no doubt at a profit, before the year was out.

Into Politics

By 1896, the pressure on Victoria to grant incorporation to several Kootenay towns had become irresistible and Nelson became a city on March 18th. The Tribune immediately presented its editor as a candidate for Mayor against The Miner’s man, John Turner. Accusations and rebuttals filled the next few editions (See John Houston: Politician) until the vote on April 15th secured Houston’s victory.

For the next eight years, Houston remained official publisher and editor of The Tribune. It continued to support his political and business interests although his many absences must have left the day to day work in other hands. Purely as a business venture it is difficult to know exactly how successful it was and, towards the end, Houston claimed that he had “lost $20,000” keeping it afloat. That end came in 1905 shortly after Houston had resigned his last mayoralty and disappeared from Nelson for the next two years. In 1907 he briefly reappeared to run for the legislature but was defeated and so left Nelson for good.

A Fitting End

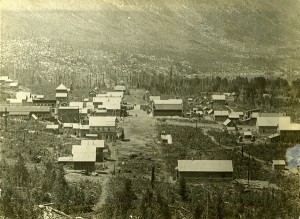

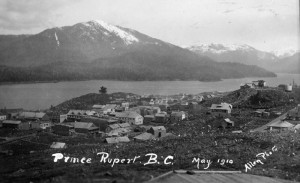

Prince Rupert, where Houston returned to the newspaper business by establishing his second to last paper, The Empire

A year later, John Houston, newspaper man, reappeared in Prince Rupert where he established The Prince Rupert Empire, once again attacking railroads, promoting mining and real estate, and defending the rights of working men. Prince Rupert at that time was the terminus of The Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad and wanting no part of Houston, tried to prevent him from buying GTR land for his newspaper office. Mining claims, however, trumped property ownership and the wily Houston simply filed a claim in the centre of town and set up shop. The company’s next move was to impound Houston’s press but they again found themselves outfoxed when editions of The Empire arrived by mail from Vancouver. The press was eventually liberated from the rail company’s warehouse and put to work re-establishing his reputation for mining expertise and colourful journalism. Unfortunately, with the steady enmity of the GTR against him in a company town and advertisers afraid to antagonize their most powerful customer, Houston lasted only a year and after a brief sojourn in Mexico, moved to Fort (now Prince) George where he established his last newspaper, The Fort George Tribune. It would be the death of him.

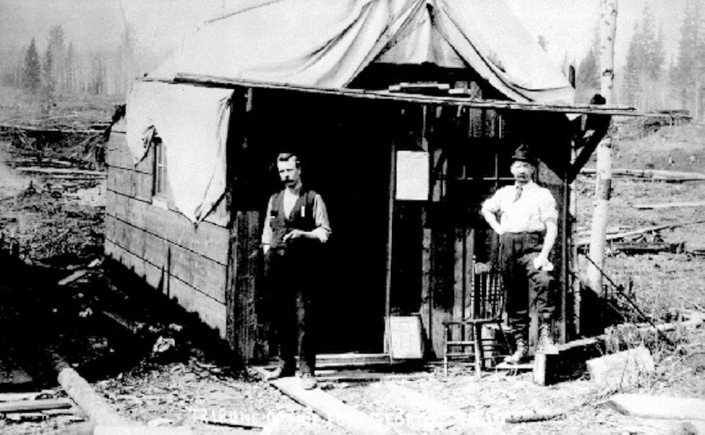

Guaranteed good advertising revenue in a booming region, he experienced financial success but paid the ultimate price. Living and working in a canvas and board shack at constantly freezing temperatures broke his health and pneumonia set in. Almost a week’s travel to hospital in Quesnel finished him off – but not without a moment of grim comedy which he no doubt appreciated. Rumours of his death reached Victoria and on March 4th his obituary appeared in several Victoria and Vancouver papers and was copied across the province. Houston’s response was typical. To the editor of The Vancouver Province he wrote

I didn’t know I was dead until your paper came out and even then I might have questioned the accuracy of the information if I hadn’t known its reliability. Don’t be putting in any correction – I’ll make good on the story.

And on March 8th, 1910, at fifty-nine years old, he did.