Setting The Stage

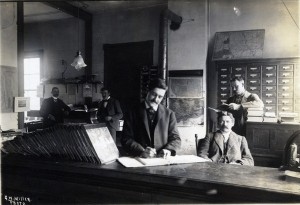

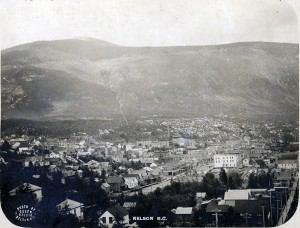

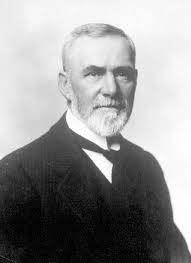

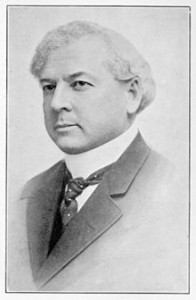

Whether intentionally or not, John Houston began running for mayor the minute he stepped foot in Nelson – or at least he began to demonstrate the kind of civic leadership that would make him an ideal candidate when the opportunity finally arrived seven years later. From the pulpit of his newspaper, The Miner, which had a readership throughout the province and the American northwest, he presented himself as the voice of the Kootenay while promoting the region’s mineral potential and campaigning for less cumbersome mining regulations. Closer to home he called for better postal service and railed day and night against the CPR whose oppressive labour practices and excessive land grants threatened (in his opinion) the very future of his city. He recruited Edward Arthur as the town’s first doctor, (seducing him away from the CPR, no doubt to his great satisfaction), subscribed to the first school, and advertised for investors and tradesmen with descriptions of Nelson’s rosy future. As a businessman, he identified himself with enterprises that involved the growth and prosperity of Nelson – Consumers’ Waterworks and The Nelson Electric Light Company – as well as real estate development and the construction of commercial buildings in the downtown core.

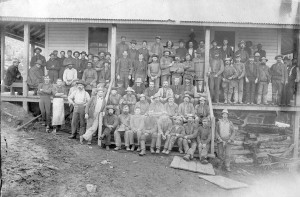

Houston also clearly positioned himself on the left of the political spectrum as a populist defender of working men and small shop keepers against big business – the mining, lumber and transportation companies and their allies in the Victoria Legislature. As a champion of the Kootenay, he soon realized that the region was quickly attaining an economic importance to the province which far outweighed its political power and, as early as 1893, began to campaign for the incorporation of Nelson. Unfortunately, fear that Houston’s real motive was to get local taxpayers to bail out his struggling electric company kept many property owners from signing the required petition.

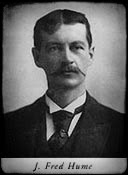

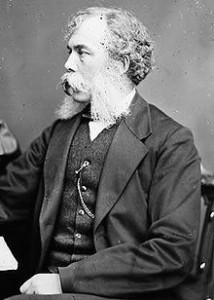

Undaunted, Houston turned directly to provincial politics and served as agent for the popular local merchant J. Fred Hume’s successful bid for office in 1894. In recognition of the Kootenay’s growing importance, Hume became Minister of Mines and was able to bring in legislation giving BC miners the eight hour day. At that time, the provincial legislature was not organized along party lines but was a chaotic mix of elected members representing moneyed interest groups adhering to a number of powerful leaders. Between 1890 and 1900, the province had six premiers and became so dysfunctional that, in 1900, Prime Minister Laurier dismissed Lieutenant Governor Robert McInnis and appointed Sir Henry Gustave Joly De Lotbiniere. Three years later, this gentleman was to have a decisive effect on Houston’s political career.

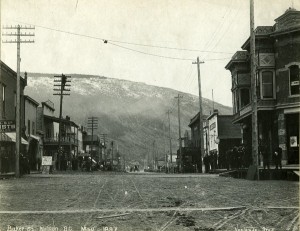

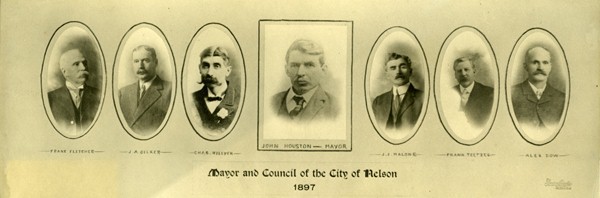

In the meantime, Houston continued to pursue his business and newspaper interests while working towards incorporation. By 1896 a number of Kootenay communities were pressing for city status and, not wanting to be left behind, (rival Kaslo had become a city in 1893) the Nelson business community finally agreed to support Houston’s petition. On March 18th, 1897, Nelson was incorporated and elections were set for April 15th. But the race for mayor and aldermen was already well underway.

The election campaign quickly developed into a two-way fight between Houston and local businessman John Turner, each mayoralty candidate carrying with him a full slate of aldermanic contenders. Among the latter’s allies was Dr. Edward Arthur whom Houston had recruited almost ten years before. Turner was backed by the white collar interests, the professionals, and adherents to big business. He was supported by The Miner, which Houston had sold in 1892 and was now the voice of what passed for Nelson’s upper crust and whom Houston referred to as “white-shirted hobos.” Houston, of course, was endorsed by his own paper, The Tribune and carried with him most of Nelson’s working men, small merchants, and hotel/saloon keepers. His aldermanic slate, in fact, contained no less than three of the latter.

On most issues the candidates were in agreement – “responsible governance” in the form of moderate taxes and licence fees, development of water and sewer services, street improvements and the principle that Nelson, as Houston expressed it, “will be … what it has been as a town, that is, clean, free and orderly.” But the weapon that Turner’s supporters hoped to use against Houston was, once again, the fear that he would use the city’s borrowing power to purchase the Nelson Electric Light Company and thereby line his own pocket at the taxpayer’s expense. This, of course, was not an issue that could be supported by hard fact – it was simply a matter of trust and Houston met it head on in an “open letter” to voters printed in The Tribune five days before the election.

The men who started that cry, and have so persistently kept it up, know that there is no basis of truth for it. The shares of The Nelson Electric Light company are held by some forty people, who are, with one exception, residents of Nelson. The company is a growing concern, and if Nelson grows as rapidly as it is expected to grow, the shares of the company will be so good an investment that holders will not be disposed to sell them even to the city. One thing you can all rest assured of, and that is, that the Nelson Electric Light company’s plant will not be turned over to the city of Nelson until a majority of the ratepayers say by their ballots that they want it and must have it.

As election day approached, the campaign rhetoric grew increasingly heated. For his part, Houston maintained a calm defensive posture with occasional explosions of scorn and ridicule directed at The Miner – but very little towards Turner himself whom he knew to be respected and well-liked. He pointed to his and his aldermanic allies’ record of civic accomplishment and hosted meetings in various saloons where the drinks were on the house. He also joined battle over eligible voters and declared that those threatened with being struck off the list should “call at the Houston committee room, corner of Vernon and Ward Streets, where they will be advised as to their legal rights.”

On the other side, The Miner poured forth a steady stream of reasoned argument, heavily laced with its own brand of scorn, contempt and character assassination. An editorial on March 27th stated,

Nearly every resident of Nelson recognizes that the health of the community is seriously threatened unless the city is supplied as soon as possible with adequate sewerage and waterworks systems. They realize that the municipality is only empowered with the right to borrow $50,000, and that a very great portion of that sum will be needed to pay for the labour which will be employed on those works. They are fully aware of what the results would be if a mayor and board of aldermen were elected who would apply this money to the purchase of The Nelson Electric Light company’s plant, or the still more useless Consumers’ Waterworks company. They also appreciate the value of franchises now possessed by the city and do not propose to see them given away to mere speculators.

And again, on April 8th,

The merits of Mr. Turner and his fellow candidates are becoming more and more recognized and established….With the office seekers on the other side, however, the case is different. The lash of the boss has been vigorously applied and his few supporters are doing as they are told with much gullibility and meekness. The enthusiasm – doubtless born of a desperate anxiety to finger that $50,000 which the boss exhibits – at first became slightly infectious with those who took pride in remarking he had more brains than themselves. With masterly logic they declared, “It will be all right to elect Turner’s opponent if we have enough reputable businessmen on the board of aldermen to prevent him doing anything reckless.’

The writer then went on to enumerate “the many failures that [Houston] has made as a promoter of certain enterprises,” even going so far as to state that, upon the closure of the South Kootenay Board of Trade which Houston organized, “no one appears to know what has become of the valuable furniture which the subscribers’ money purchased.”

Such accusations were commonplace in the rough and tumble of pioneer politics and, to the typical Houston supporter, doing what he might be tempted to do himself was not likely to be held against him. Nor was the assault charge laid against Houston a week before the election – for punching a Turner supporter in the face – considered particularly serious, even though, as The Miner pointed out when he was subsequently convicted and fined, “This is the third conviction of assault that appears upon the police records since Houston has resided in Nelson.”

In the end, Houston’s personal popularity with working class voters, his prestige as a newspaper man, and a general conviction that he and his team were men who ‘get things done’ won the day. Of eligible voters, 88% (519 out of a possible 589) cast ballots, 58% for John Houston, 39% for John Turner. Interestingly, 16 ballots were not marked for either candidate. His entire slate of aldermen also triumphed, winning 62% of votes cast.

That night, in a meeting at the Nelson firehall, Houston was presented with a gold headed cane (now on display at City Hall) and a silk hat and, as reported next day in The Tribune,

The spectacle of John Houston under a silk hat provoked much merriment……After the presentation the mayor-elect was escorted to a carriage, and A.J. Marks marshalled about one hundred shouting men and boys into line. The Nelson brass band formed the head of a big procession and proceeded to pump melody into the noise of the crowd. A rope was attached to the carriage in which Houston was seated and a dozen of his most prominent workers drew him through the principal streets, followed by a good natured crowd carrying lighted brooms. The fun was kept up for hours.

Civic Accomplishments – Battles Lost And Won

Houston and his aldermen immediately set to work and created an impressive list of accomplishments in an impressively short period of time. In the nearly twenty-one months between mid-April, 1897 and the end of 1898, (Houston was returned by acclamation in January, 1898) he and his councils built a new bridge over Ward Ck. at Baker St., erected a provincial goal, improved streets and laid down sidewalks, dug a new reservoir above Anderson Ck., established street lighting -contract to Nelson Electric Light – created a fire alarm network throughout the city, made much needed improvements to the city’s sewage system, and passed a by-law requiring new buildings to install brick fire walls between themselves and their neighbours (for which we can thankfully credit the survival of so many architectural gems from that period).

Not that all this was accomplished without grumblings from the opposition. Complaining of “boss rule,” The Miner reported friction between the mayor and his aldermen as he began to gather as much power into his own hands as possible. The Municipal Act at that time was vague about how much executive authority a mayor could exercise and undoubtedly Houston stretched it to the limit, taking over licensing, the appointment of civic employees – including police and firemen – as well as public works purchases. He awarded the city’s printing and advertising contracts to The Tribune without going to tender and, in an act described by The Miner as “wanton extravagance,” accepted a salary of $2,000 a year. There was also talk that he and the police chief exacted a ‘fee’ of $10 a month from those gambling dens and brothels which wanted to avoid periodic closures.

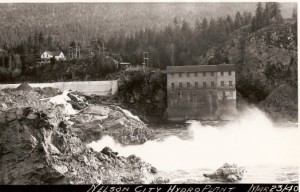

In the spring of his second term Houston fulfilled the expectations of supporters and opponents alike by introducing a by-law to borrow money for the purchase of the Nelson Electric Light Company. As much as $40,000 was talked of but not even Houston’s audacity was up to passing such legislation without a referendum. Taking the lead in opposition was Dr. Arthur, arguing that the company was vastly over-priced and the power generation capacity of the Cottonwood Falls plant would never meet Nelson’s needs. On June 9th, the referendum was declared defeated by nine votes. A few days later, however, after Houston ordered a recount, the by-law was passed with a majority of two.

According to historian Edward Affleck, “Dr. Arthur went to his grave believing the ballots had been tampered with, and claimed that many years later one of the polling officers had confessed to him that indeed there had been irregularities in the polling.” A few weeks later, Arthur petitioned the court to overturn the vote on the grounds of those irregularities as well as conflict of interest – pointing out that Houston and no less than three aldermen were directors of Nelson Electric. In October victory again appeared to be Arthur’s as the court ruled in his favour but just six weeks later an appeal to a higher court restored the by-law.

Houston had prevailed, but at the cost of his job. In the 1899 election, the opposition rallied around local businessman George Neelands giving him both the victory and the problem of what to do with Nelson Electric. After purchasing the company for $35,400, the city added water to Cottonwood Ck. via a flume from Whitewater Ck. When this proved inadequate, they began negotiations to buy surplus power from West Kootenay Power and Light, owned by a consortium of big business interests with connections to the CPR. This, of course, was anathema to Houston who was returned to office in 1900 with promises to fix the problem (but at a reduced salary of $1200 a year). Unfortunately, he only managed to make matters worse when a newly-built dam designed to create a storage reservoir on Cottonwood Creek burst, the water and debris carving a path of destruction across the CPR flats and into the Kootenay River. Wisely, Houston did not run for re-election in 1901 but by then he was well into the second phase of his political career as Member of the Legislative Assembly for The City of Nelson.

Stepping Onto A Bigger Stage

Just before the 1900 provincial election, J. Fred Hume temporarily retired from politics to devote his attention to running his hotel which still stands today at the corner of Ward and Vernon Sts. leaving the door open for Houston to try his luck. While the legislature was not yet organized along party lines, candidates did register themselves as meaning to support or oppose the government and also gave themselves descriptive designations. Houston ran as a government opponent and as a ‘Progressive’. His opponents were former municipal ally Frank Fletcher (Conservative), whom Houston had just defeated by ten votes in the mayoralty election, and Dr. George Hall (Independent Liberal). Houston won handily with 48% of the vote. Furthermore, the opposition, under the coal and timber baron, James Dunsmuir, found themselves in the majority and ready to form a government.

By 1900 the West Kootenay had become a going concern both economically and, by extension, politically, growing from two ridings (North and South) in 1894 to four in 1898 (Nelson, Revelstoke, Rossland, and Slocan) and adding a fifth (Kaslo) in 1903. Hume had served as Minister of Mines and so it was not unreasonable for a Kootenay MLA, especially one of Houston’s stature, to expect consideration for a cabinet post as well. In haste, he set off for Victoria but soon returned empty-handed.

When the legislature assembled in the fall, however, Houston was there and, such was his reputation for eloquence, his maiden speech was awaited with much interest – and for some time, in vain. Finally, after sitting in silence for several weeks, Houston rose and gave a rambling speech attacking his own government’s tariff bill, apparently misunderstanding the significance of a particular amendment and calling a prominent government supporter “a mossback” (according to Websters – an extremely old-fashioned or reactionary person). It was also clear that he had been drinking. Worse was to follow. That same evening on the street outside, he insulted and attacked Simon Fraser Tolmie, then secretary of the Mine Owners Association and a future premier of BC. Unfortunately, Tolmie, a solid individual and seventeen years his junior, knocked him down and bloodied his nose.

Such behaviour might have earned Houston censure had the government been able to do without him but, with the slimmest of majorities, they were clinging to power by the skin of their teeth. Nor was he censured when, drunk once more (by his own admission on “only four or five big jorums of Scotch whiskey” although he used this to assert that he therefore could not have been drunk!), Houston railed against the government, insulted the Speaker, and refused to leave the chamber for over twenty minutes. Finally, he exited with the declaration that “The sooner we bring this disreputable legislature to an end the better.” All this played well with the rougher elements of his supporters back home in Nelson but it was to have dire consequences for his prospects of political advancement.

Meanwhile, back in Nelson, Fletcher became mayor for two terms (1901-02) and worked out a deal with West Kootenay Power and the Nelson Electric Tramway Company whereby surplus capacity for the city’s power grid was purchased from the latter which had in turn purchased it from the former. The city then set about obtaining water rights on the Kootenay River at Bonnington Falls with the intention of building its own plant there. Houston also kept his hand in municipal politics, forming The Progressive Party and, in 1903, successfully running W. O. Rose as his chosen candidate.

By 1903, the BC legislature had organized into parties and, ironically, the Conservatives had positioned themselves as champions of workers’ rights and legislation favourable to progressive labour. Perhaps as surprisingly, given his erratic conduct, Houston was chosen its president, although in fairness his hard work and eloquence during more sober moments had won him back a considerable measure of respect.

Fall of the Mighty

With Dunsmuir’s resignation in November, 1902, Edward Prior assumed the premiership and called an election for the following June. His association with Nelson Electric well in the past, president of the Conservative Party and a shoo-in for a cabinet post, Houston defeated his Liberal rival, Sidney Taylor with 54% of the vote. Surely now he stood at the pinnacle of political power and in triumph he set out for Victoria where everything seemed to be in his favour. There was even talk that he, not the 33 year old Conservative leader Richard McBride, should be premier – although the modest Houston merely asked to be made either Provincial Secretary or Minister of Lands and Works. And indeed, with the government possessing the slimmest possible majority of 2, with a Speaker yet to be appointed, it seemed impossible to deny him.

But, on October 23rd, McBride informed him that the impossible had happened – that Lieutenant Governor Sir Henry Gustave Joly De Lotbiniere had refused to accept his appointment “on account of the unfortunate incident of last session, when you forgot what was due to the legislative assembly as well as to yourself, in your responsible position.”

McBride could have insisted. Indeed, allowing the Lieutenant Governor to reject the advice of his premier on such personal grounds ought to have precipitated a constitutional crisis. But the sad truth was that only Houston himself and his supporters far away in Nelson were outraged. Such a potential personal embarrassment, such a highly vocal and deadly enemy of big business could not be allowed into the inner sanctum of government and if McBride did not in fact engineer the entire business, he was undoubtedly satisfied with the outcome. As for his slimmest of majorities, he formed a most unholy alliance with the various Socialist members and ruled BC for the next twelve and a half years.

Four days later, an interview with a crestfallen and obviously disheartened Houston appeared in The Victoria World,

You can say for me that I will not be a member of the McBride government. No, nor of any other government. You can tell them in The World that John Houston is going to go back to Nelson, that he is going to close up business there, and that he going to leave British Columbia for good and for all…I am done. You can put it that I am done…..I expected to be used at least decently. But yesterday I got the dirtiest deal that ever a white man got in the province of British Columbia.

Returning home to Nelson his friends rallied round him, expressing their indignation and sympathy and so, in the end, Houston did not pack his bags nor close up business. But it must have been extremely galling to such a man to live among neighbours who had undoubtedly greeted his downfall with glee. For the next year he spent very little time in Nelson, dividing it between Victoria where he occasionally attended the legislature and various prospecting expeditions.

Comeback

By the end of 1904, however, Houston had recovered enough to once again run for mayor – this time against his former ally (a common theme), Dr. Rose. As little had been done to further the development of Nelson Hydro’s plant at Bonnington Falls, Houston must have been anxious to salvage the one solid achievement of his career. Both candidates promised to bring in a borrowing by-law and to get the job done, so it all came down to a matter of who could best do it. Nelson chose Houston and three months later work began – only to be quickly halted by an injunction obtained by West Kootenay Power, granted by Judge Irving. In the spring of 1906 the injunction was denied by the BC Supreme Court and the power plant moved towards completion. But by that time, John Houston had left Nelson and, with one brief exception, he had left for good.

Frustration in his political career and a lack of business success brought about by losses from the sale of The Houston Block and running The Tribune, had begun to take their toll. Always a man with a temper and used to getting his own way, ‘the boss’ had lost his charm and had turned into a mere bully. From the mayor’s chair he attempted to run the city as his own personal kingdom. Matters came to a head when he fired fireman and wagon driver Samuel Coulter while refusing to give his reason. Over the next three months mayor and council wrangled back and forth, reinstating and dismissing Coulter with comic regularity. When council removed Houston’s power to fire the driver, he invoked his power to ‘suspend’ him. Finally he gave his reason for the dismissal as drunkenness and when he could provide no evidence of this, Houston baldly stated that it was because Coulter was not a supporter of his Progressive Party. This was too much for Progressive aldermen Macdonald and Annable who switched allegiance and voted to put all municipal hiring power into the hands of council. With that, Houston, who was in Victoria at the time, abruptly disappeared and nothing was heard from him for the next six weeks.

Then, in early October, just as council was about to declare the office of mayor vacant, having previously reduced his salary to $1 a month, a letter arrived from Goldfield, Nevada.

I should have dropped a line before now but as I was a wanderer, I thought it best to defer writing until I had a post office address. I have been here a month and shall remain for a time.

He then wrote a description of the town and its mineral prospects reminiscent of early description of Nelson in The Miner, and continued,

I might write something personal but the least said the better. The decision of Judge Irving disgusted me; that decision coupled with the fact that I seemed to be unable to make any headway in business developed a fit of despondency. It was continual worry, and borrowing from Peter to pay Paul. I am discredited. I am broke in my old age; but I gave Nelson and its people the best that was in me for fifteen years and every dollar I made is still in evidence in Nelson in property that is paying taxes. The debts I left will be paid if I live; for I have good health and there are just as many chances to get ahead now as in former years. I sent in my resignation as mayor today to take effect at noon on Monday, October 23rd. The council showed its calibre by passing that $1 a month motion; but then, all things will come right in the end. Houston

This might reasonably be thought the last act of a political career but Houston still had an epilogue to play out. In 1907, McBride called an election and on January 9th, The Nelson Daily News (formerly The Miner) announced that Houston was returning from Goldfield to contest the election  as an independent in Ymir. After a short and somewhat lacklustre campaign, he ran third in the polls with 21% of the vote behind his old rival J. Fred Hume (33%), and Conservative William Schofield (46%). In Nelson itself, George Hall, the Liberal candidate whom Houston had defeated in 1903, won by 5 votes over the Conservative.

as an independent in Ymir. After a short and somewhat lacklustre campaign, he ran third in the polls with 21% of the vote behind his old rival J. Fred Hume (33%), and Conservative William Schofield (46%). In Nelson itself, George Hall, the Liberal candidate whom Houston had defeated in 1903, won by 5 votes over the Conservative.

As suddenly as he had come, John Houston left the Kootenays and did not return until the occasion of his municipal funeral in 1910. In 1915, his friends erected a monument to his memory which stands on Vernon St. at the heart of the city between the Court House and J. Fred Hume’s hotel.