The Formation of a Bang Up Fire Company

The chances of a British Columbia mining camp turning into a full grown city during the last decade of the 19th century were comparable to those of a tadpole becoming a frog. There was fierce competition to snag the regional railway terminus and all the trade that went with it. Mines and smelters had to keep producing. Ore prices had to stay high. Good postal service and government agency offices must be established and maintained. Most of all there had to be a solid core of hard working businessmen with forethought and determination to make their community prosper – men (occasionally women, but mostly men) who gave of their time and money to establish the institutions that would sustain it through all possible disasters – economic downturns, floods, and fire. And no institution was more vital to the growth and prosperity of a pioneer town (a town built almost entirely of wood) than its company of firemen.

From its earliest years, Nelson was blessed with (or achieved through the above mentioned forethought and determination) all of these qualities thanks to local merchants such as J. Fred Hume, R. E. Lemon, W. J. Wilson….. well, just look at the list of contributors, printed in the January 20, 1894 edition of The Tribune when those three gentlemen “passed around the hat on Friday and raised enough to pay for the hose-cart, hose, and other appliances that have been at the Columbia & Kootenay freight depot for over two months.” Prominent among them too was the writer of said article, Tribune editor, aspiring politician, and by his own account the most generous contributor, John “Truth” Houston.

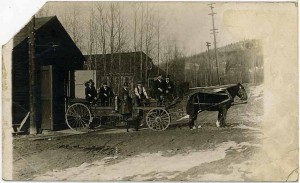

By that time Nelson was well beyond the mining camp stage but well short of city status (incorporation wouldn’t come until the spring of 1897). But already a volunteer fire brigade had been established. As told by historian Greg Nesteroff, “When Nelson’s volunteer fire department formed in early 1891, the first order of business was deciding on a name. It required several speeches and ballots, but according to The Miner, Finally the organization was christened Deluge Hook and Ladder Company No. 1 of Nelson and the man who proposed the name was sprinkled with muddy water from a floor sprinkler, much to the amusement of the friends of the defeated names. In those days, there were no horses much less motorized engines and a fire department’s worth was measured by how fast its members could pull a hose reel or chemical wagon.”

Over the next three years several fires were fought with varying degrees of success. The first was recorded in the April 9, 1892 edition of The Miner. With a net loss after insurance of $3,000 (about $80,000 in today’s dollars), this was serious business.

But just over two months later a much greater disaster was narrowly averted when logs and brush fires set by street clearing crews at several locations along Victoria, Silica and Carbonate Sts were blown out of control by strong winds coming down Cottonwood Creek. Fortunately, The Miner reported, there was length enough of hose to attack [the fire] from the hydrant at the corner of Victoria and Stanley.

This tells us a number of things; first, that nothing had been learned from the Vancouver fire of 1886 where the entire city had been wiped out with large loss of life from exactly the same cause; secondly, that a number of fire hydrants had already been set up at various points near the centre of town; and thirdly, that “a length of hose” but apparently no other equipment, was available to the brigade.

Nevertheless, it took well over a year and two fundraising balls before fire fighting apparatus was ordered and yet another fire, which destroyed the International Hotel on Vernon St., to finally spur the formation of, as Houston put it, “a strong, active, well-drilled fire company.” Characteristically pulling no punched he added that “The membership of the present company is made up of men not active enough to be effective at a fire.”

Thus on January 23rd, 1894, when The Deluge Hook and Ladder Company No. 1 held its annual meeting in the dining room of The Nelson Hotel several prominent citizens stepped forward to reorganize and re-energize the company. The town doctor, E.C. Arthur was elected president, and sixteen men enrolled as ‘active members’ (volunteers) “to be exempt from the membership fee (one dollar) and monthly dues (fifty cents) and to be paid an annual stipend of $18.”

Thus on January 23rd, 1894, when The Deluge Hook and Ladder Company No. 1 held its annual meeting in the dining room of The Nelson Hotel several prominent citizens stepped forward to reorganize and re-energize the company. The town doctor, E.C. Arthur was elected president, and sixteen men enrolled as ‘active members’ (volunteers) “to be exempt from the membership fee (one dollar) and monthly dues (fifty cents) and to be paid an annual stipend of $18.”

With $969.25 in revenue and $874.42 in expenditures, $227.83 in resources and only $115 in liabilities, the company had finally been put on a strong financial footing and (Houston again). “The fire hall will be fitted up to allow of four of the active members lodging in the building. The apparatus will all be put in serviceable condition, and Nelson will ere long have a bang up fire company.”

A new fire hall was built at the cost of $400 in which was kept the hose reels and a new hook and ladder wagon. When the city finally ordered it to be dismantled in 1925 The Nelson Daily News recalled that dances, meetings, and entertainments of all kinds were held there in the early days. A famous entertainment was that given there by the ladies of Nelsonwhen they provided a New England dinner, at fifty cents a head, to raise money for a bell for the fire hall. The new bell arrived in September and it was announced that it was a very fine oneweighing about 300 lbs.The ladies made $89 by their dinner and the bell, including duty and freight, cost $72. The difference was turned over to the fire hall.

A new fire hall was built at the cost of $400 in which was kept the hose reels and a new hook and ladder wagon. When the city finally ordered it to be dismantled in 1925 The Nelson Daily News recalled that dances, meetings, and entertainments of all kinds were held there in the early days. A famous entertainment was that given there by the ladies of Nelsonwhen they provided a New England dinner, at fifty cents a head, to raise money for a bell for the fire hall. The new bell arrived in September and it was announced that it was a very fine oneweighing about 300 lbs.The ladies made $89 by their dinner and the bell, including duty and freight, cost $72. The difference was turned over to the fire hall.

An unknown author writing in the 1950’s left us this colourful description of the early days.

The drivers were well qualified in the care of the horses and horse drawn apparatus. In winter months, the wheels were removed and sled runners were installed with utmost care, owing to the extreme downhill grade to the business and mercantile area. Surprising as it may seem, the city was protected by two stations, one located in the 500 block Observatory, along with one at the present location of the Nelson city electrical substation .”

The apparatus stationed in the Observatory hall was drawn by two horses named Bob and Duke. The apparatus in the other was drawn by horses named Barney and Jerry. Residents were amazed and awestruck by the precision training and general intelligence of the horses upon receipt of an alarm. At the strike of the gong each horse without command would promptly exit from their respective stalls to a position in front of the wheel or sled apparatus. The harness would be dropped on to the back of each horse and with precision the duty firemen would make two snaps of the harness beneath the horses. Many opinions differ as to whether the driver issued the command of “guddap” or the horses departed immediately, challenging the driver to mount the driver’s seat at time of response. Here, the glory of charging horse-drawing apparatus, along with a tobacco chewing fireman was most evident, and thrilling to John Citizen. The highly spirited horses were keenly instinctive of direction and fire area.

The City Takes Over

When Nelson was incorporated in the spring of 1897, The Deluge Hook and Ladder Company No. 1 passed into history and became The Nelson Fire Department under the control of Mayor John Houston and his council. Its first chief, appointed in October of that year was 26 year old Samuel F. Calkin, who had previously been a fireman in Vancouver. The chief’s was a salaried position (a handsome $80 a month) but it would seem that steady wages were not for him. Just two months later he resigned and headed for the Klondike.

Next up was a more mature (33) William Jiggens Thompson who almost immediately came into conflict with Mayor Houston over what Houston considered his lax approach to building inspections and insufficient oversight of the company payroll. After a grilling before council, he managed to keep his job but he was finally forced out in December, 1901 at the end of Houston’s third term.

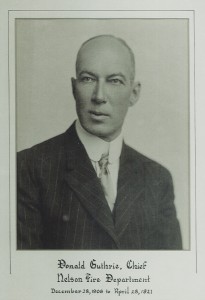

This political warfare between mayors and chiefs continued intermittently over the next ten years. Thompson’s successor, 50 year old Thomas Lillie, was suspended twice by Mayor Frank Fletcher apparently because of animosity created by reports that Lillie had spoken disparagingly of the mayor to an insurance salesman. In 1905 Houston, back for his fourth term, clashed with Chief Thomas Sargent when Houston tried to fire a wagon driver who was not a supporter of his municipal political party. This ended badly for Houston when council sided with chief and driver. In fact for this and other reasons, Houston left Nelson halfway through his term and resigned a few months later. On the other hand, Sargent was dismissed in 1906 for drunkenness. Finally, in 1910, bickering between council and Chief Donald Guthrie lead to the latter’s resignation although a petition of businessmen persuaded him to withdraw it. He then went on to a long career as chief and died in office in 1921.

This political warfare between mayors and chiefs continued intermittently over the next ten years. Thompson’s successor, 50 year old Thomas Lillie, was suspended twice by Mayor Frank Fletcher apparently because of animosity created by reports that Lillie had spoken disparagingly of the mayor to an insurance salesman. In 1905 Houston, back for his fourth term, clashed with Chief Thomas Sargent when Houston tried to fire a wagon driver who was not a supporter of his municipal political party. This ended badly for Houston when council sided with chief and driver. In fact for this and other reasons, Houston left Nelson halfway through his term and resigned a few months later. On the other hand, Sargent was dismissed in 1906 for drunkenness. Finally, in 1910, bickering between council and Chief Donald Guthrie lead to the latter’s resignation although a petition of businessmen persuaded him to withdraw it. He then went on to a long career as chief and died in office in 1921.

But politics aside, the first decade of the city run department saw many improvements, the most important occurring almost immediately. In 1897, Houston’s council passed a number of fire related by-laws including a requirement that new commercial buildings in the downtown core construct brick firewalls on either side. This led to almost all buildings being built of brick or stone – many magnificent examples of which survive, in restored glory, today.

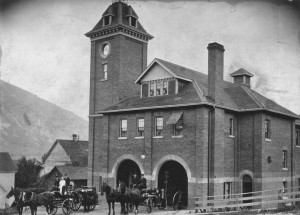

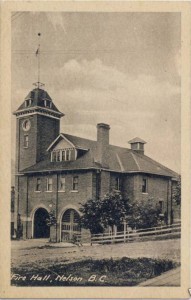

The fire hall at the corner of Victoria and Josephine was expanded and fully quipped and as noted above, a second hall on Observatory was set up in 1898. It was upgraded in 1908 but then taken out of service when the present fire hall at Ward and Latimer was built five years later.

Other improvements undertaken during Houston’s mayoralty included the installation of additional hydrants as the water system was expanded , the addition of a team of heavy horses (Barney and Jerry) and the purchase of a new and larger bell. This bell, it is worth noting, was discovered to be flawed and had to be replaced by guarantee in August 1902. Unfortunately this one cracked the following spring during a practice alarm, The Tribune reporting that “there are now over one thousand pounds of bell metal around the fire hall but the city is without a fire alarm that can be heard for more than two blocks.” Bell number three, costing $200 and manufactured by a different foundry (Meneeley & Co., West Troy, New York) arrived in February 1903 and Jacob Dover, through whom the purchase was conducted states that the bell will be found to be a good one and is reported to have added that if it is not in shape one hundred years hence he will come back and treat “the crowd” to cigars. Since the bell can still be seen at the present Nelson Fire Hall, Mr. Dover has never been called upon to keep his promise.

Nelson’s volunteer department became partly paid in 1901 with a full-time chief, assistant chief, and teamster plus ten volunteers who each received a monthly stipend of $15, less $2 for missing a call. By the end of Chief Guthrie’s tenure in 1921, the paid staff had grown to five with the addition of two more drivers.

Nelson’s volunteer department became partly paid in 1901 with a full-time chief, assistant chief, and teamster plus ten volunteers who each received a monthly stipend of $15, less $2 for missing a call. By the end of Chief Guthrie’s tenure in 1921, the paid staff had grown to five with the addition of two more drivers.

A New Hall

The following is excerpted from an article in The Nelson Star written by Greg Nesteroff:

On May 20, 1913, the Nelson Fire Department moved into its new headquarters at the corner of Ward and Latimer Street, a brick building considered the most modern of its kind. A century later, the department is still there, in what’s now BC’s oldest operating fire hall (no one disputes the title which was recently affirmed during a meeting of provincial fire chiefs in Nelson).

In 1909, then-fire chief Donald Guthrie pleaded with city council for a new hall to replace the one at the corner of Victoria and Josephine streets built 15 years earlier, which he described as “poorly located, unsanitary, and dilapidated.” He got his wish but it took until June 1912 to approve the funds.

The new hall was designed in Italiante Villa style by city engineer G.C. Mackay and built by contractors John Burns and Son for $17,973 (over $367,000 today). It came in under budget but slightly behind schedule due to boiler problems. According to Nelson: A Proposal for Urban Heritage Conservation, the location was initially dismissed by citizens as too far from the city’s core, but it proved a wise decision given the growing Uphill residential district and proximity of several schools.

The original floor plan showed the basement with a coal room, boiler room, and battery room that powered the alarm system. The second floor had accommodation for the chief and ten firefighters and the ground floor had room for two wagons and five horses — two teams and a spare — plus a grain bin and hay room.

“The fire hall basically was a stable for horses as opposed to a garage for trucks,” says current chief Simon Grypma. “Instead of waxing fire engines they would have been feeding, brushing, and washing the horses and checking their hooves instead of air pressure in the tires.”

A recently re-found and digitalized video gives a glimpse into the fire hall and its role in the community, showing school fire drills and the new fire hall with its horse drawn engine.

A shore article about this video was featured in the Nelson Star in the spring of 2014.

Yet times were changing, for less than six months after the fire hall opened, the city decided to buy its first motorized fire engine, an American LaFrance that arrived in 1914. Horses and vehicles then worked side-by-side for a decade until the department finally dispensed with its equine employees.

This lantern was passed on from the original horse wagon to the new La France Soda acid truck purchased in 1913.

Retired fire horses (who included Barney and Jerry and Bill and Dick) found jobs on milk wagons or garbage duty but reportedly had a hard time adjusting, for upon hearing the fire alarm they would gallop off, spilling their wagon loads behind them.

The completion of the hall coincided with the installation of a new electric alarm system. Thirty-five boxes were scattered throughout town. Tripping the switch notified the fire hall and a gong relayed the call’s location through simple code. For instance, two bells, a pause, and three more bells meant box 23.

To combat false alarms, dye was placed on the boxes and local teachers knew any student caught with green fingers had likely been up to no good. The punishment was spending a Saturday polishing fire trucks. The boxes were finally retired in 1980 even though they still worked well (a couple are in the fire hall’s museum).

The building underwent major alterations in 1948 when it was re-roofed in aluminum and galvanized steel. The cupola atop the hose drying tower was removed and the original arched doors for the horse-drawn wagons were enlarged and squared off so automatic doors could be installed.

In 1956, chief Owens suggested building a second hall in Fairview, but the idea didn’t go anywhere. By 1979, then acting chief Sommerville told city council improvements were urgently needed and recommended replacement. By that time the hall was severely overcrowded and the concrete floor was cracked from the burden of multi-ton trucks — one of which was parked without cover at the city works yard because there was nowhere else to put it.

The city seriously considered building a combined fire department and police station, but times were tough and instead the hall received $90,000 worth of restoration and renovation that included adding an ambulance station on the lower side. The foundation was also stabilized, the sheet metal roof replaced with cedar shingles, the red and white paint scheme removed in favour of the original brick, and a new cupola built by Selkirk College students.

Talk of replacement

The present chief, who has worked in the building for more than one-third of its 100 years, is proud of its longevity but says it isn’t without its headaches. “The biggest challenge we face today is the size of equipment,” Grypma says. “Backing the trucks into the hall during the winter, the front ends want to slide downhill. City council [of 1912] never imagined engines as big as they are now.”

Talk of a new fire hall still comes up occasionally, most recently in 2010 when Fairbank Architects pegged the replacement cost at $5 million. Since then, the hall has received about $250,000 worth of work, particularly in energy upgrades after an audit found the building was one of the city’s biggest culprits for greenhouse gas emissions due to lack of insulation. “In the next few years I think there’s going to be some serious planning on replacement,” Grypma says, “but I’m hoping this fire station remains an historical site.”

Less About Politics, More About Fighting Fires

Returning to that anonymous description from the 50’s:

At the beginning of World War I, Nelson city fathers in their wisdom purchased the first motor-driven apparatus, an American La France triple combination pumper c/w chain drive, with solid rear tires. With much sadness on the part of the public, horses Bob and Duke were retired to pasture up lake, there to spend their remaining days.

Hereon as all departments the Nelson Fire Dept. entered a new era of firefighting procedure. After a series of experiments and fires, the council authorized the chief to construct a pumper on a commercial GMC chassis and retire the two remaining horses Barney and Jerry. The GMC pumper rendered reasonably good service to the year 1938, at which time it was replaced with a Ford/Marmon Herrington triple combination pumper. Chief Donald Guthrie, Frank Boyd, Jack Ballantyne, Murdoch Maloney along with Gordon McDonald governed and supervised all fire department activities up to the year 1954.

By 1951, there were 14 full-time firemen when Chief Gordon Macdonald undertook to trim their ranks to eight supplemented by 30 volunteers. Resistance from the firemen culminated in a mass resignation of the entire body. This backfired when their resignations were accepted by the city and a full complement of men were hired. Today the department consists of the chief, assistant chief, a fire prevention officer, two shift captains, six firefighters, a secretary-dispatcher and 21 on-call auxiliaries. While the department still awaits its first full-time female firefighter, it does have one amongst the auxiliaries.

Some of the above stories originally appeared in the Nelson Star as part of Greg Nesteroff’s series on the history of the Nelson Fire Department.